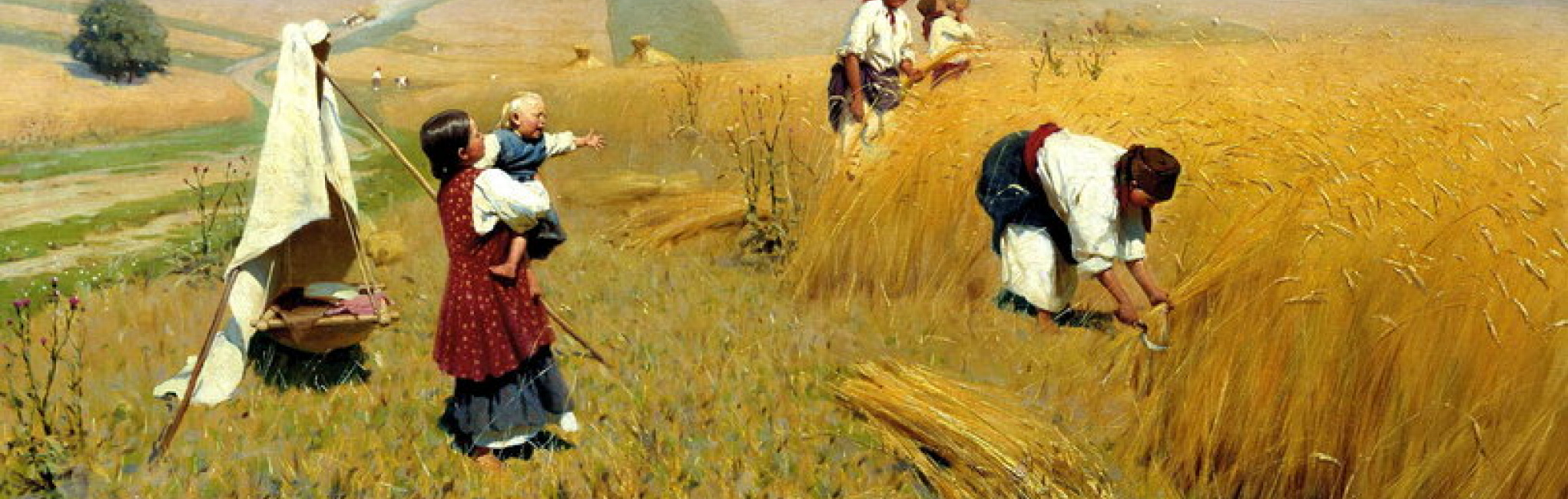

Mykola Pymonenko. Reaper. 1889

The wedding functioned as an initiation rite to mark a female’s transition from the demographic group of girls (‘divchata’) to a cohort of married women, molodytsi. The wedding ceremony included a number of transition rituals that assured the bride acquired the status of a woman (covering the head, the komora rite). This status was symbolic for a certain period and became real with the birth of the firstborn (‘pervistok’).

Ivan Sokolov. Wedding

he position, rights, and powers of women in the Ukrainian patriarchal family should be considered in terms of the family divisibility custom. It resulted in almost all territory being controlled by a small (nuclear) family. Therefore, in a rural family, a woman and a man usually built a partnership. It cannot be said that the partnership was equal as the husband remained the head of the family and all important decisions were his prerogative (although usually discussed with his wife). However, women had considerable economic autonomy within the family and were often able to dispose of domestic resources.

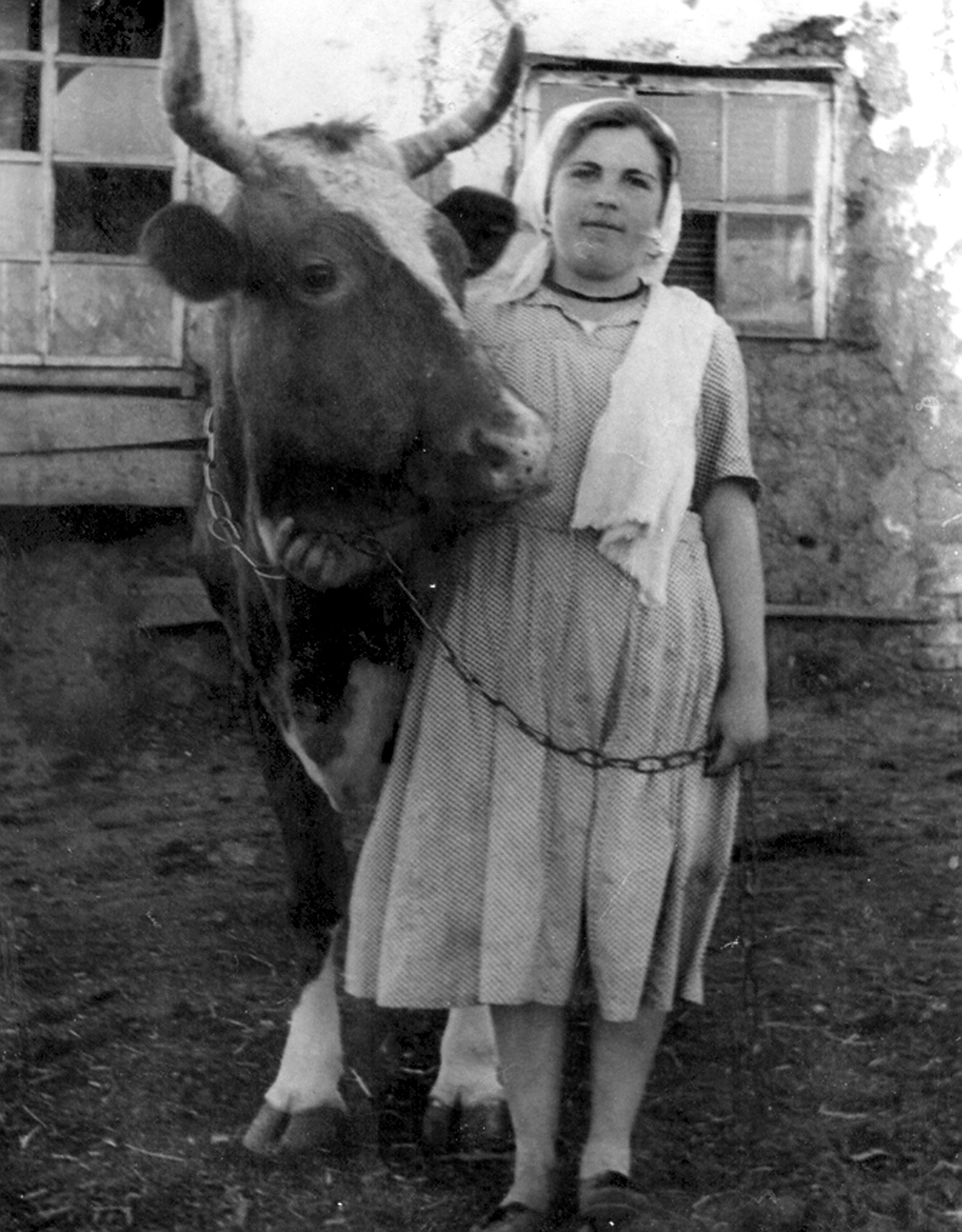

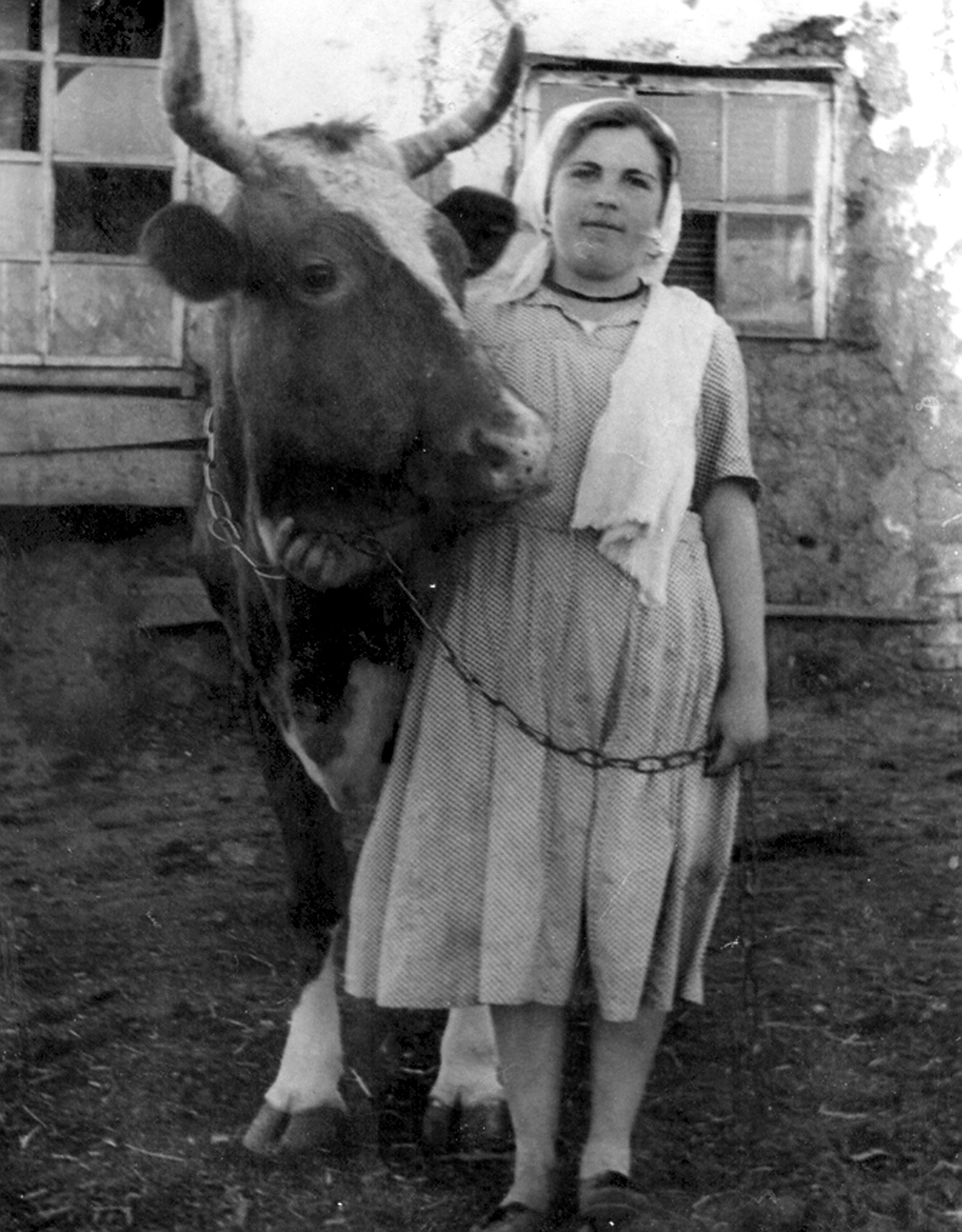

Ksenia Nechai. Approximately 1955. Village of Lukhny, Illinetskyi raion, Vinnytsia Oblast.

In Ukraine, patrilocality was widespread and required that a wife move to her husband's house after marriage. However, there were situations when the husband settled in with the wife's paternal family. This man was called a pryimak. This typically happened if the father-in-law had no sons. The son-in-law, not the daughter, would usually become the householder after the father-in-law's death.

Parents usually prepared their daughter a

posah (‘dowry’) upon marriage that included a

skrynia (‘chest’) with

ryshnyky, bedding, clothes, etc., and cattle. Once the couple was married, the dowry remained the property of the wife, although it was shared within the family. Without the consent of his wife, the husband could not dispossess this property (grant, sell, or exchange it). As a rule, land was not given as a dowry for the bride. Wealthier families who could afford it were exceptions. In this case, the woman could pass this land on to her children; this piece of land was called

materyzna (‘maternal’).

Mykola Pymonenko. Harvest in Ukraine. 1896

After marriage, women became housewives. Her area of responsibility, as a rule, was confined to the house and homestead, in contrast to the man whose main economic activity took place outside the home. In traditional society, there was a clear division of labour by sex. Women's responsibilities included: cooking, raising children, producing, repairing, and washing clothes and other things for the family, taking care of family members if necessary, keeping the house and yard in proper condition, taking care of pets and poultry (together with her husband), dairy farming, gardening, and field work (sowing, weeding, harvesting).

Large Lipivsky family, 1943 Golynchyntsi village, Sharhorod district, Vinnytsia region

A woman's reputation as a good housewife guaranteed her high status in the community. She had to skillfully manage the household, increase wealth, take care of family members, organise family life in the right rhythm, and follow the calendrical annual and weekly routine. Calendrical rituality self-organized the community and contributed to its stability and order. The woman had a leading role in following the folk calendar and correctly performing its customs and rites. She executed and managed the preparation process for celebrations (pre-holiday cleaning and decoration of the house, prepared festive clothes for family members, arranged the holiday table, among other tasks) as well as monitored fasting, bans on work, and prepared and ate modest meals during the week (Wednesday, Friday).

Woman. 1925. Village of Kozyntsi, Lypovets raion, Vinnytsia Oblast

Women widely used magical practices in their daily lives including healing as well those designed to ensure success in business, avert negative influences, or get rid of problems.

Friends. 1950. Village of Yakymivka, Orativ raion, Vinnytsia Oblast

Responsibility for procreation and the socialization of children was laid first of all on the women. A woman’s key social role was motherhood. Babies were also looked after by elder family members (usually grandmothers), or older children because women sometimes did not have the opportunity to pay the child enough attention as they were often overloaded with household chores. The cult of the body and its correlation with folk morality constitutes a separate chapter in women's history. Loss of virtue before marriage was considered shameful for both the girl and her parents. The birth of an illegitimate child was considered a brutal violation of the norms of morality and coexistence in a rural community. Women who birthed illegitimate children were called pokrytky (‘cover-ups’) and had the lowest status in the social hierarchy.

Children, 1957, p. Sokil, Chernivtsi district, Vinnytsia region

had special status in traditional Ukrainian society. According to the customary law of Ukrainians, after the death of her husband, the widow became the main successor of the household. This provided the widow with an equally high place in the social hierarchy. At the same time, widows were treated with compassion, as running a household on their own was challenging for single women.

Harvest of oats by Christian cooperatives. The photo was taken by a soldier of the Austro-Hungarian army in the summer of 1915 in Halychyna.

http://www.coop-union.org.ua/?p=9329

In general, a woman has a significant household workload in agrarian society. Simultaneously, women tried to unleash their creative potential and express their aesthetic tastes and skills in work such as as vyshyvannia (‘embroidery’), sewing clothing, painting, and pysankarstvo (‘Easter egg painting’), leaving a legacy of folk art for their children and grandchildren. Despite the fact that most forms of women’s work were performed within the family, there were a number of women’s specialisations implemented at the community level: kukharky/varylyhy (‘cooks’) who were invited to weddings and funerals; znakharky (‘sorceresses’; witches in the olklorised and demonised adaptations); baby-povytukhy (‘midwives’), holosilnitsi (‘mourners’), and pysankarky (‘Easter eggs painters’), among others. Almost all women's activities were accompanied with singing — a demonstration of creativity and a means of relieving emotional tension and improving moods.

Women carrying adobe. 1964. Village of Zhyvotvka, Orativ raion, Vinnytsia Oblast

To conclude, women in patriarchal society played a significant role in intra-communal communication, and ensured customs and traditions were followed both in their own family and within the rural community. To a large extent, the economic and moral well-being of the family depended on women. They had the most responsibility in procreation and raising children. They were the bearers of creative folk practises such as songwriting, house design, sewing, culinary skills, and the organisation of celebrations.