Link copied

December 10, 2021

Place and significance in the countryside; the relationship with ornament; the ritual and semantic nature; the diversity of stories and genres.

Bertold Brecht made the following statement on folk painting: “The bad taste of the masses is more deeply rooted in reality than the tastes of intellectuals”. But now, taste and bad taste have undergone significant changes. It is unlikely that there are minimally educated individuals who deny the value of art that was once considered questionable, bazaar, kitsch, and trash. However, the primary epithet of this art was its ‘market value’. Although the first examples of folk painting date back to the 1920s, their mass production and distribution began in the first postwar years, and reached their apogee in the 1950s,actively continuing until the late 1970s. Then, their mass appeal began to notably decrease. The reasons for this decrease were socio-existential processes that took place in the Soviet countryside.

Throughout most of the 20th century — until the last quarter — the countryside slowly changed, but retained the communicative and cultural foundations that have long determined its spiritual traditions. Simultaneously, a number of changes, particularly regarding increasing interaction between the village and the city through the bazaar, allowed folk painting to fit in the rural environment. Ornamental imagery was seemingly the predominant genre possible there. Folk painting — with its particular temporality — managed to overcome farmers’ long-standing bias towards figuration, principally pictorial and portrait imagery.

We can consider the traditional interior of a country house to be a completely cosmological-sacred environment. There is nothing superfluous here, and domestic minimalism prevails. The introduction of folk painting into this environment should be regarded as the result of social and existential dynamics in the countryside. A slow process occurred whereby the village was distanced from nature and migrated into everyday comfort. As comfort and wealth increased in the countryside, the social and figurative significance of folk painting changed. Folk painting served civilizational and historical functions such as the expression of the farmers’ dream of a beautiful life, about the heavenly unearthly world of permanent celebration, overseas exotics, romantic visions, fantastic phenomena, ceremonial folklore, and mystical actions.

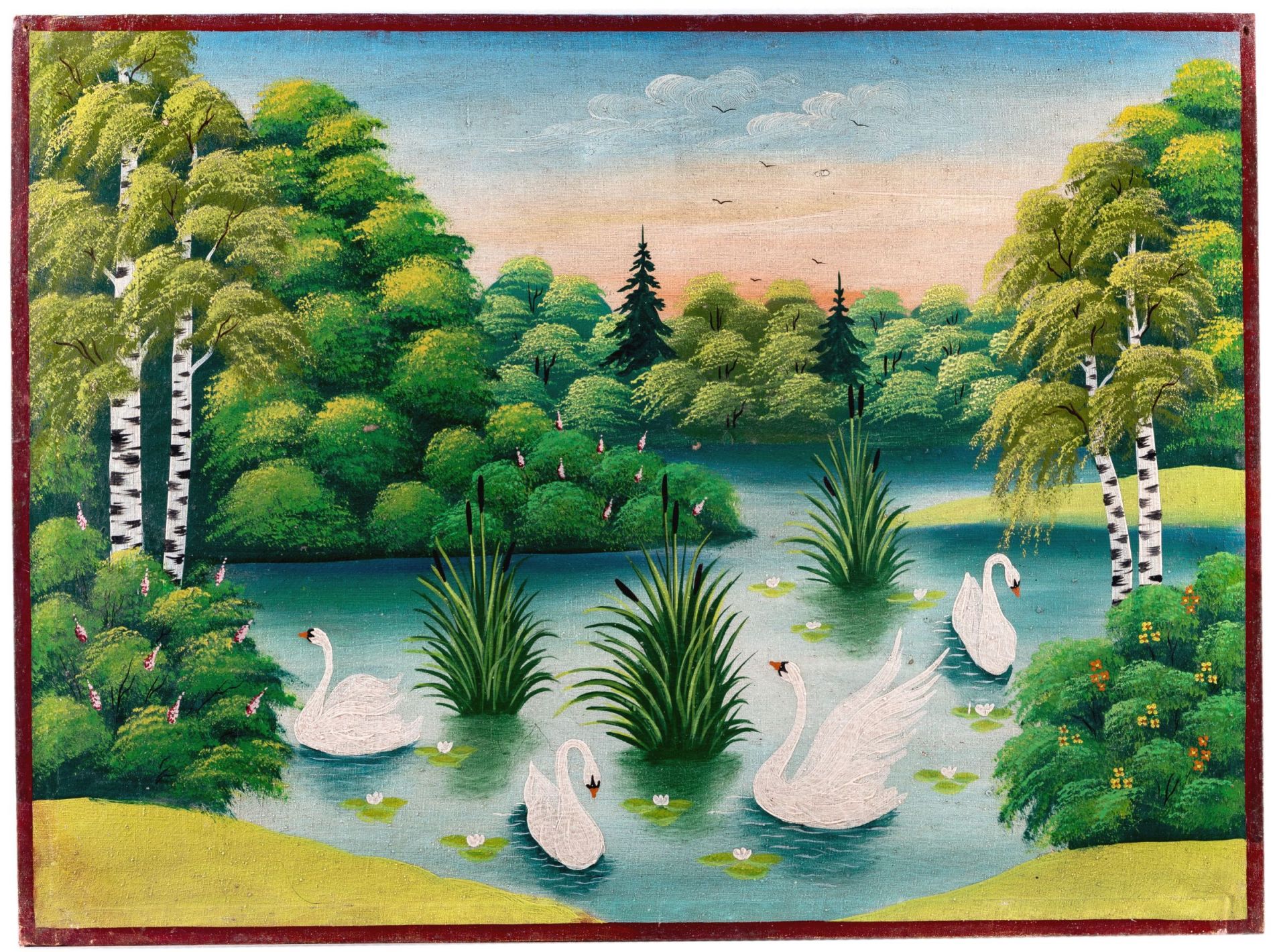

One of the predominant types (or genres) of folk painting was made on glass, plywood, or cardboard, and is commonly attributed to the category of market kitsch. In this case, I consider the latter as a positive phenomenon, designed to bring figurative realities, or rather, their conventionalised decorative image, into the sacred-ornamental space of the country house. Examples of these images are numerous sentimental and small paintings: 'Girl with Flowers', 'Girl with Cats', 'Two Girls', 'Girl and Boy', and 'Two Cats' and greetings or marriage-greetings depicted on glass with silver and coloured foil: 'Doves among Flowers', 'Male Dove and a Female Dove with a Leaf in its Beak', 'Flowers with Doves', 'Flowers', and 'Faith, Hope, and Love'. These images emphasize the naive faith of the farmers in harmony and prosperity and demonstrate the cosmological reality of 'eternal peace'. In general, folk painting is the manifestation of metaphysical realities of existence, but it is not limited to the aesthetics of natural subjects (sunset, castle with lake and swans, swans on the water, deer on the shore) or fairy-tale and allegorical-metaphorical plots (girl with a deer, being taken to the 'other' side in a boat with the help of swans and angels, and 'Angel watches over children’.) Folk painting also has a didactic factor.

The planar-decorative principle, the rhythmic application of colour, and the presence of complete or partial symmetry build bridges between folk painting and ornament. These principles and techniques help to create a world of perpetual presence, without past and future. This world is close and familiar and at the same time unattainable in its illusory perfection.

The schematic and formal character of greeting images with symmetrical pairs of doves and text (such as ‘In memory', 'Wishing you happiness', 'Greetings', 'Let happiness beat its wings on your destiny, as a swan beats its wings on water') derive not from ornament directly, but from murals and figurative elements, in particular the symmetrical birds, and kitsch, sentimental greeting cards. The resemblance of ornament, the specificity of figures and subjects, semiotic structure, semantic openness, and the clear symbolism of images (swans, pigeons, deer) give folk painting the properties of an 'enzyme' in the countryside house when faced with the new social and existential reality. Therefore, the artisanal and semantic formula of folk paintings ersatz ancient traditions that could no longer fully meet the vital needs of farmers.

In these conditions, the traditional yet innovative creativity of rural artists was shaped. Some well-known artists that exemplify this tendency are Hanna Sobachko, Kateryna Bilokur, and Maria Pryimachenko. However, there were numerous lesser-known folk masters, amateur performers, master craftsmen, and artisans who were creating folk paintings. Folk paintings had an ‘enzyme-like’ property — also characteristic of photography, radio, electricity, and socio-organisational activities — that stimulated and intensified the process of re-semantization of the rural environment, the environment of small towns, and the suburbs of large cities.

A defining feature of Ukrainian folk painting is exemplified by ‘Cossack Mamai’ with its parsuna and iconic poetics, its seriation, and variability.

The plot and image are replicated with slight variability on the dominant features. The variations are selectively constructed depending on the tastes and preferences of the inhabitants of particular regions or centres. But given the limited scope and overview of this essay, I will not delve into a detailed analysis of regional plots and archetypes, the characteristics of genres and styles, or the figurative specifics of folk pictures in different localities and areas of Ukraine. I will limit myself to a list of the plots and genres that were most ‘popular’ among farmers and, accordingly, were the most common throughout Ukraine.

The plot ‘People go to Church’ was one of the most widespread throughout nearly the entire Ukrainian territory. It is composed of a gentle, sunny landscape with an elegant and impressively depicted church, people dressed in festive attire heading towards it, and village huts symmetrically arranged on both sides.

The image of a castle on a lakeshore with swans was quite common. Dense and often blossoming trees grow around the castle, a lake reflects the pink sunset, and white swans that swim on the dark water give the picture a mysterious, romantic mood.

In many regions, a rural landscape with a river, a pond, the same swans, a fisherman in a boat, and neat toy-looking huts was also common. The typicality of this landscape is a reference to the notion of ‘eternal peace’ — an ontological moment of presence.

The same landscape was often depicted at dusk featuring a red-pink and orange sky burning in the west and reflected in the water of a lake or river. From the depths of the image, a chthonic darkness emerges that generates disturbing, eschatological premonitions. Simultaneously the special colour of the red-pink burning sky gives some works a romantic mood.

The landscape of a village or town featuring neat houses, windmills, and a church built upon a mountain that looms above a river was quite common, in particular in the villages of Middle Naddniprianshchyna. The image is brought to life with the depiction of fisherman on a boat or an old-wheeled steamer sailing down the river. The latter is predominant in paintings created in the 1920s and 1930s.

The traditional rural still life featuring a watermelon, a bottle of wine, flowers, and fruits became widespread. This still life was considered a symbol of familial harmony and well-being. One can call it a ‘greeting’ still life.

The folk painting ‘Cossack and a girl near the well’ occupies a prominent place in folk plots and genres. This plot emerged in folk paintings around the mid-1920s. Earlier samples either did not exist or have not been studied by researchers. ‘Cossack Mamai’ and the works of Mykola Prymonenko informed the heart of this plot. In his unpublished work, K. H. Skalatskyi points at the icon ‘Christ and the Samaritan Woman at the Well’ as another possible plot origin. The painting ‘Cossack and Girl…’ can be divided into three genre variations based on certain compositional and stylistic features which can be titled as:

- Tragic conflict (dramatic). The meeting of a Cossack and a girl is presented as the meeting of two worlds: the warmth of the home and comfort contrast the windy steppe, battles, campaigns, wandering, and vagrancy. In the story of a soldier and a girl meeting near a well, their relationship brings not only love but also suffering. After all, the fate of the Cossack dictates sacrificial love composed of long periods apart in wait for the desired meeting again, all the while, facing the risk that the Cossack may die in battle or be captured.

- The meeting of a Cossack and a girl under ordinary living circumstances. The Cossack is deprived of the strict warrior’s features and attributes, and the girl is well dressed as if preparing to meet a loved one. This plot is often accompanied with a caption such as: ‘My girl, give the horse a drink ’ or ‘Give water to drink from a full bucket’.

- Instead of the ontological drama, a melodramatic and burlesque deliberation dominates. In some cases, the Cossack is depicted as an ordinary country boy wearing a bryl (hat) and playing an accordion, and the girl is listening to him play and sing, while pouring water past the bucket into the ground. Another more common composition, captioned 'Run, Petro and Natalka, for mother is coming with a rolling pin', concerns the plot of a famous painting by Mykola Pymonenko.

Another fairly common image in Ukraine is ‘Angel Guards the Children’. This plot has two predominant situational variations:

- an angel stands in a protective gesture extending his hands over a boy and girl who are playing on the edge of the abyss;

- an angel guards two children (a boy and girl) who are crossing a river or stream on bridge-masonry in the morning.

These plots are prominent n in a number of European countries; however, they are most frequently found on German postcards, in books, and in magazine reproductions. Some of them date to the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The plot with the Angel and children is common in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Poland, but it seems to have only acquired the status of folk painting in Ukraine.

The mysterious painting ‘Olenka and a Deer’ is widespread across Ukraine and is most likely associated with the ancient phenomenon of totemism. The girl and the deer are depicted as a married couple, surrounded by flowers and wearing flower crowns. Based on the girl’s clothes and other details, it is likely this plot emerged from Western European fairy-tales and mystical spheres. It is reminiscent of another well-known story, ‘Girl with a Unicorn’.The paintings ‘Olenka and a Deer’ and ‘Angel Guards the Children’ are simplified, folklorised, equivalents of their modern European counterparts.

‘Being Taken to the ‘Other Side’,popularly called ‘Rusalky’, is a no less mysterious painting. It reproduces the nocturnal glamorous and mystical scene already described above. The soul of the dead is pictured as a sleeping woman in a luxurious boat, towed by a pair of swans, and led by an angel. They are moving towards the chthonic nocturnal darkness of the afterlife. The boat is accompanied by beautiful and well-dressed mythological female creatures, rysalky. There are no doubts about the non-local origins of this plot as it contains characteristic features of European sentimental-mystical modernism of the late 19th century.

There are also sentimental and glamorous modern plots featuring ladies in a boat feeding swans or pigeons, waiting for someone, sitting in a gazebo on an island, and so on. They were also distributed en masse, but lacked a single style or dominant plot or genre.

Paintings based on the plots of popular folklore or literary works (for example, 'Kateryna', 'Bondarivna', 'I was Thirteen', 'Taras Bulba with his Sons', 'House Maid', 'Oh, the Fire is Burning on the Mountain') and a variety of their editions did not become widespread.

In conclusion, it should be noted that folk painting comprises a stage in the cultural life of folklore, which is constantly reproduced in various formal and figurative manifestations. Its plots, landscapes, and minor forms; greetings, and fragments introduced the spatial and temporal reality of life through figurative form into the spacetime of the rural house. At the same time, folk paintings contained metaphors, myths, and folkloric cosmological symbolism.

Folk painting as an environmental phenomenon has lost those features that aroused the interest of the rural population — for example, it has declined as a socio-cultural phenomenon — with the changing socio-political context. t However, as an artistic phenomenon, it has persisted as the manifestation of folkloric reality, the bearer of archaic symbolism, metaphors, and archetypes, and it was revealed as one of the artistic-cultural phenomena of modern life.