Link copied

December 06, 2021

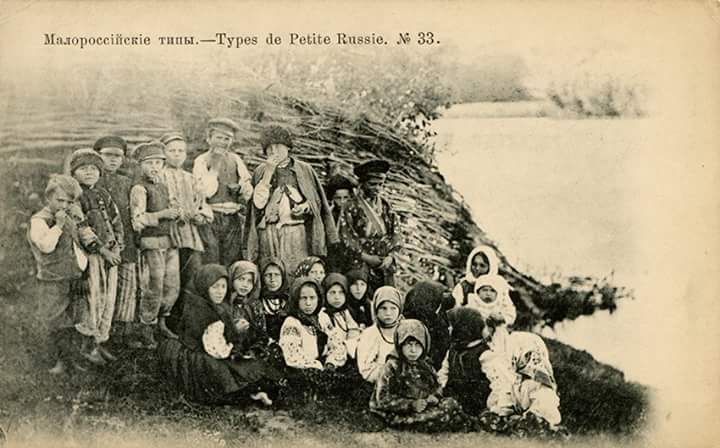

Unlike modern society where, from birth, the child is highly valued and perceived as a unique individual whose needs are placed higher than the needs of adults, in traditional societies, the philosophy of childhood had its own wisdom. Some people, through their modern lens, might interpret it as ‘backward’ and ‘wrong’, but the culture of care, upbringing, and education that children in an agrarian patriarchal society received (combined with children's game and work practices) were aimed to best adapt the child to survival and self-realisation. The central idea of raising children was not to allow parents to become accustomed to their child’s needs and desires gradually, step by step, and to introduce them to society with the help of social institutions (kindergarten, school), but on the contrary — to immediately, and as much as possible, fit them into the rural way of life. The birth of a child should not have disturbed the established work rhythm of the family; a child’s earliest physical skills, mental faculties, and imitative features were immediately used by adults to help in the household where extra arms and legs, dexterity, and a keen eye were always needed. Such involvement in labour from an early age was seen as the key to success from the standpoint of adults in a patriarchal society. For example, a young woman who gave birth for the first time already had experience watching after a dozen (or even two dozen) children, namely younger brothers and sisters, cousins, and neighbours. Therefore, she performed the demands of motherhood almost without stress.

It should also be taken into consideration that until the 20th century, infant mortality was extremely high worldwide. The saying: ‘The Lord gave and the Lord has taken away’ was not a metaphor, but a harsh reality and at the same time a kind of psychotherapeutic formula to help parents survive child loss. The mortality of infants and children in the first year of life was especially high. This fact resulted in, firstly, a certain modesty and ‘unpretentiousness’ (from our point of view) of birth celebrations, and secondly, a large number of superstitions and taboos surrounding childbirth. The principle of avoidance was the most important ritual at this stage: the newborn child, and for some time its mother, had to be isolated from the outside world. This folk custom was based on common sense and centuries of experience in caring for babies. It complies perfectly with modern sanitary and hygienic rules, although this behaviour was interpreted through folk beliefs (danger of ‘vroky’, i.e the evil eye).

The first person the newborn baby ‘met’ was the baba-povytukha (‘midwife’) who together with the woman who just gave birth and her closest relatives (mother and mother-in-law) was considered the ‘safest’ person for it. It was these women who took care of the child and the mother in the first days after birth.

In some regions of Ukraine, people practised odvidky: they visited a woman who gave birth and her new child. Women (relatives and friends of the young mother) brought the products necessary for the woman's recovery after childbirth (honey, bread, pies, cereals), as well as baby care items (mostly clothes). In many places, visits were not practised until the child was baptised. Khrestyny (‘christening’) was the primary ritual event a person experienced in the first period of their life. It consisted of a church rite of baptism, when the child received an official name, and a celebratory feast. For this ritual, which is common today, parents choose kymy (‘godparents’); often they consist of two individuals, although in some areas in the past people used to invite several couples. They were solemnly invited either by the child's father or the midwife. The godfather took bread and the godmother took kryzhmo, a piece of cloth on which the child is held during the church ceremony, do khresta (‘to the cross’). After the church rituals, people celebrated the event with family and neighbours at a festive table at home. Sometimes the holiday continued on the second day as people arranged pokhrestyny (‘after-christening’).

In the past, a parish priest was directly involved in choosing a child's name. He turned to sviatsy (‘menologium’), a list of saints, martyrs, and righteous people whose names were assigned to each day of the church calendar. However, the child was not called with its name for a long time as adults replaced it with euphemisms. In the Ukrainian language, there is a very rich folk terminology to denote children of different ages. Different age categories are fixed in folk terms, denoting the child's acquisition of various skills and abilities. For example, in the first year of life a child might be referred to as narodzheniatochko, pyskliatochko, maliatko, smiiaka, bezzubyi did / baba, belkotun / belkotukha, sydun / sydukha, lazunets, etc..

In the past, during the first months of life, the child was surrounded by only a few objects. First of all, that was kolyska (or lulka; ‘cradle’) made of wood — many lullabies describe it as ‘yellow maple’, ‘nut’, or ‘twisted tree’— that was attached with a hook and ropes u svoloku (‘into the main beam of the house’). Children's everyday life was modest and even ascetic by our standards: the cradle resembled a simple box, and diapers, for softness, were made of old shirts. The main ‘decoration’ was given in oral tradition. In particular, in children's songs the cradle appeared to be ‘painted, with silver strings’, with ‘silver bells’, with ‘golden headboards’, with ‘silk bedding’, ‘down pillow’, or ‘silk clothes’.

For a long time, breastfeeding was the baby’s only food. To feed and calm the child, people made a kukla (‘doll’), composed of chewed bread wrapped in cloth.

Childcare was mainly a collective task undertaken by the mother, grandmother, and older children in the family, mostly girls. One of the keys to a child's health and harmony in the family was a child's peaceful sleep. The Ukrainian folk culture of childcare includes a rich practice of performing kolyskovy pisni (or kolysanky; ‘lullabies’), aimed to calm the child and ensure its healthy sleep. Not surprisingly, the most common characters are sleep and drowsiness, a cat with soft legs, etc., and the texts themselves have a magical spell-like nature ('Oh dreams, come to the lullaby, lull the baby’; ‘Oh you white kitty, don't go around the house, don't go around the house, don't wake up the baby’).

When the child grew up and its sleep time was reduced, people turned to singing zabavlianky (‘amusing songs’) and utishky (‘calming songs’). They not only entertained the children so that they would not be bored but also stimulated their physical development. This folk genre typically consisted of a verbal part and certain performer’s actions (light body massage, petting, rubbing, bending and unbending of fingers, legs, and wrists, turning the head, gymnastics). For example, moving the child's fingers was accompanied by the words: ‘Peas, beans, goose, chicken, kikiriki!’, and the baby’s thumb was shaken at the last word. Dandling on the hands and the knees, and tossing a baby in the air were accompanied by special rhymed refrains such as: chukykalky, hutsylky (‘oh chuk chuky chuk, grandpa cooked some pikes, and grandma cooked some rumours to feed the children, and grandma cooked some crucians to feed Tarasyks, and grandma cooked perches to feed some folks’).

When the child was one year old, it got its hair cut for the first time. Sometimes these haircut rites were called postryzhyny. It was forbidden (or not recommended) to cut children's hair for the first year as it was associated with many superstitions. Otherwise, children were given embarrassing nicknames such as: khodun, shavkotun, shchebetukha, nimets. At this stage, these words were already devoid of euphemistic meaning and became terms to denote age.

Up to two years of age, (age was determined by such terms as eating the first/second paska (‘Easter cake’); the second porridge / eating the second porridge) children did not get out of their mothers’ hands’ and their living space was limited by their parents' house and yard. However, the more confidently they walked, the wider ‘their’ space became.At the age of four, they began to unite and gather with their peers in the yard.

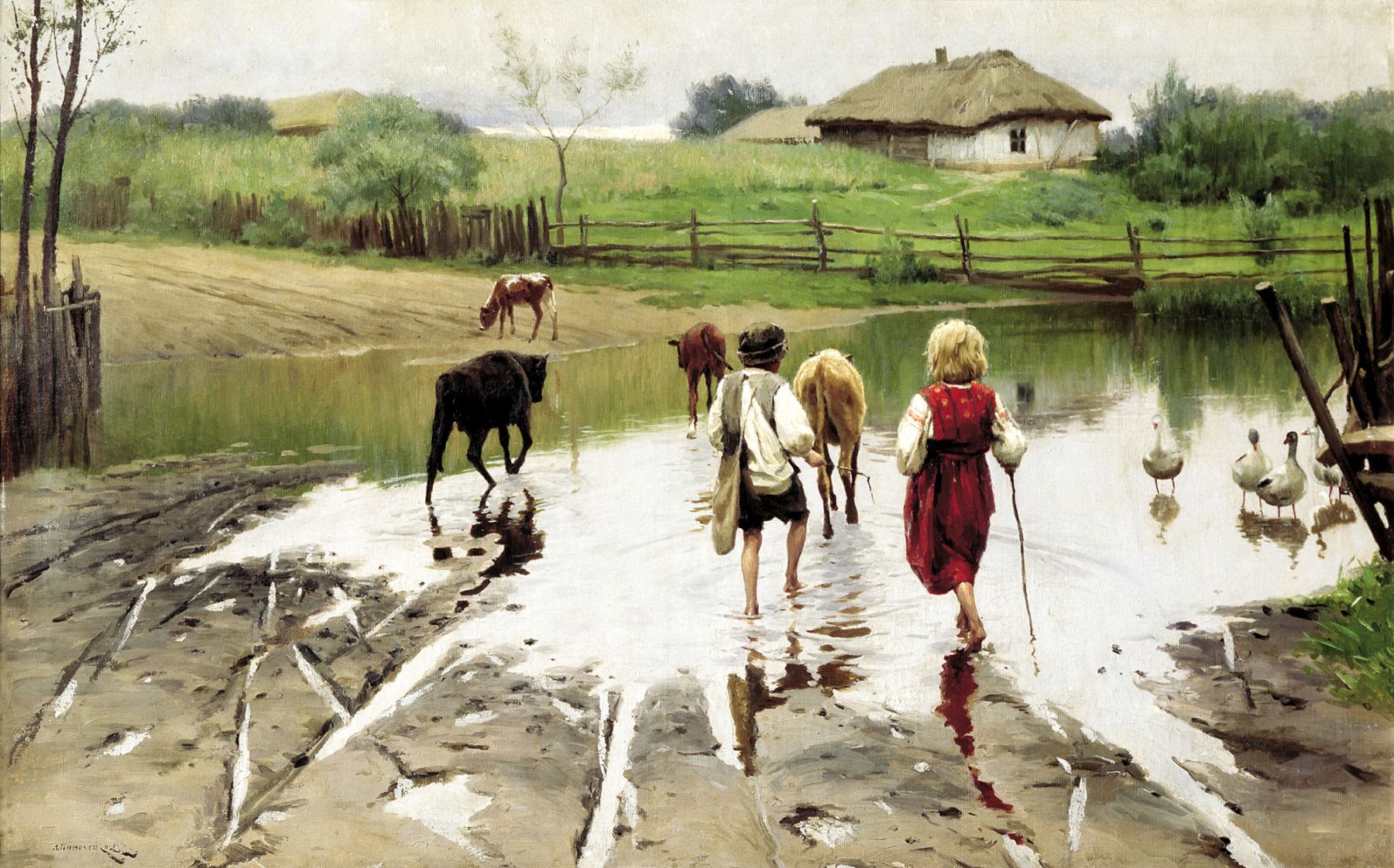

Up to 4–5 years of age, children, regardless of gender, wore long shirts. Boys were often teased with such rhymed sayings as ‘pantsless — chicken uncle’, and then children began to dress in pants and skirts. Boys' hair were cut in a boyish manner, and girls wore their hair braided and often wore headscarves. At about this time, we see recorded the appearance of their first job responsibilities such as assistance to seniors, or independent responsibilities. There were some tasks that an adult woman should never perform, for example tearing pears off a tree, lighting a lamp, and so on, and these tasks were assigned to childrenFolk terminology fixed the age of children with professional terms as pastushok, pidpasych (‘shepherd’), nianka (‘nanny’), shvachechka (‘seamstress’), priashechka (‘spinner’). If someone asked a child’s age, the answer was often: ‘Yeah, it’s already a cowherd / worker / mower'. Child labour was most often used for grazing cattle and assistance (na pobihenkakh; ‘at beck and call’), as well as fishing, and the manufacture of primitive traps for birds and small animals.

It should be noted that the work responsibilities of young children always included elements of play and helped dexterity, agility, coordination of movements, the development of fine motor skills, attentiveness, and physical strength. Children's games were also aimed at enhancing the same abilities: 'Rozha’, ‘Ripka’ (jumping on one leg), 'Derkach' (limited mobility due to the tied leg), 'Kreimashka', 'U livoruchky' (one-handed operation), 'Iashchur' (speed of redressing), 'U nozha' (skills of using tools), 'Panas' (spatial orientation, gropingly), 'Pizhmurky', ‘Palychky’ (searching skills), ‘Tisna baba’ (pushing), 'U kramaria', 'U kavuna', ‘U glioga', 'U vorona' (skills to guard something and show dexterity in catching up to others). Some role-playing games of an imitative nature had socialising, and educational functions such as Vesillia ('Wedding'), Pokhoron ('Funeral'), and Kupailo games where children jumped over nettles, built 'houses', and played haymaking.

The children's subculture included various children's folklore genres, in particular, lichylky (‘counters’) and drazhnylky (‘teasers’) such as ‘Olena is a green frog’, ‘Tymish ate too many mice’, ‘Kondrat is a brother to pigs’, rhymes imitating birds and animals, among others. Zasivannia (‘sowing for the New Year’) was the most famous of the childrens’ ritual functions. For example, boys aged 8-12 and older vodyly kozu (‘led a goat’) at Shchedra Kutia (‘at the eve of the Old New Year’), and at dytiacha koliada (‘children's carol’).

As for toys (ihrashky, zabavky, tsiatsky), the rural culture of the 19th and early 20th centuries primarily promoted children's creativity. Children made toys for themselves, the most popular options were taradaiky, vizochky (‘carts’), mlynky, pyshchyky, dzygy (‘whirligigs’) from pine bark, and svyni (‘pigs’) from cucumbers. The girls ‘rolled’ lialky (or kukly; ‘dolls’) from old rags: they made their heads by tying a ribbon around their necks, tied them with a scarf and sewed their hands, and dressed them with a skirt, aprons, and shirts. These dolls were ‘lulled’, ‘fed’ from shards (children's utensils), and involved in role-playing games. In the spring, girls made dolls out of grass and flowers. Children also made primitive musical instruments for fun: pipes, whistles, and more. In the 19th, and especially in the early 20th century, in the bazaars and fairs people were sold toys made by folk craftsmen from clay, wood, vine, paper (vytynanka) and fabric. Centres for making folk toys have developed, in particular in the town of Iavoriv, Opishni village.

At the age of 10-11 children were nicknamed pivparubok (‘half-boy’) and pivdivka (‘half-girl’) to indicate their readiness for future adult life. When they began to be called divka (‘girl’) and parubok (‘boy’) at the age of 14-16 years, it meant that the conventionalised childhood period was over.