Link copied

December 08, 2021

In an agrarian society, starting a new family has long been considered the culmination point of one’s life. A wedding is a rite that accompanied marriage and sanctioned it at the legal level. In a traditional agrarian society, girls most often married at the age of 15 – 17, and boys were married at the age of 18 – 20.

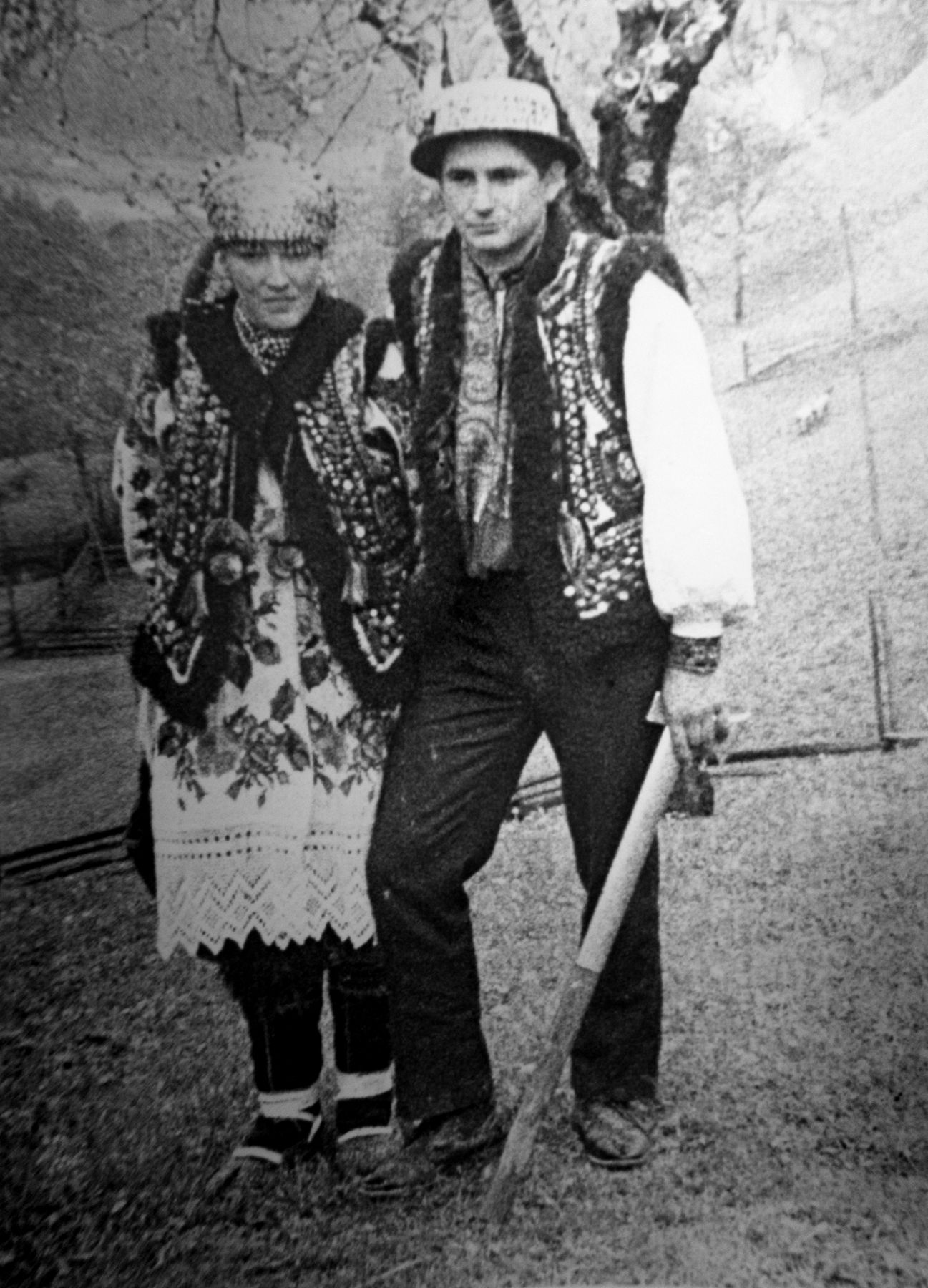

The wedding ceremony was embedded in familial ritual systems, had a complex semantic structure, and was characterised by wide variability. This was due to various factors, including geographical, historical, and socio-economic conditions, interethnic contacts, and religious characteristics, amongst others. According to wedding ceremony descriptions of the late 19th-early 20th centuries, researchers distinguish several regional types namely: central (which includes Podillia and Slobozhanshchyna subtypes), Polissia, Carpathian, and southern variants. The geographic areas of each type corresponds to an ethnographic zone of Ukraine in the late 19th-early 20th century.

Ukrainian weddings (vesillia, visilie, svadba, svalba, svaiba, etc.) traditionally consisted of many ceremonial actions that had a legal and initial/signatory nature. They were accompanied by both poetic and prose folklore texts and dances relating to various subjects.

In historical and ethnographic literature, wedding ceremonies are commonly divided into three cycles: the pre-wedding, the wedding itself, and the post-wedding cycle. The pre-wedding cycle includes rozvidky (seeking), svatannia (matchmaking), ohliadyny (the bride-show), and zaruchyny (engagements). The wedding itself involves a loaf ceremony, wedding invitations, divych-vechir (girls’ night), bride price, posad molodykh (seating of the newlyweds at the table), covering the bride, and the bride moving to her husband's house. The post-wedding cycle consists of prydany (dowrie), perezva, pyrozhyny, tsyganshchyna and other rites performed over the course of a week in honour of the parents on the occasion of their son's marriage and the daughter-in-law's entry into a new family.

The young man’s parents usually received final consent for the marriage of the couple during svatannia (the matchmaking): svatannie, svatannia in Kyivshchyna, Chernihivshchyna, Zhytomyrshchyna, Vinnychyna, Sumshchyna, Dnipropetrovshchyna, svatanky in Zakarpattia, mogorych, zmovyny in Zhytomyrshchyna, Sumshchyna, Poltavshchyna, davaty rushnyky, braty rushnyky in Kirovohradshchyna, rushnyky in Kharkivshchyna, zalioty, zhodyny in Lvishchyna, slovo, starosty in Ivano-Frankivshchyna, poslatysia, zapyty mogorych in Lvishchyna, obminiaty khlib in Cherkashchyna, Kirovohradshchyna, and pobyty poklony, podaty khustky, podaty rushnyky in Kyivshchyna.

An additional and optional component of the pre-wedding ceremonial cycle was ohliadyny (the bride-show): pechehliadyny in Zhytomyrshchyna, rozhliadyny, rozhledyny, hryzty pich, vyhliadyny in Kyivshchyna, Vinnychyna, Chernihivshchyna, Sumshchyna, Poltavshchyna, Kharkivshchyna, obzoryny in- Lvivshchyna, and pietc vazhyty in Zakarpattia. At this stage, the relatives of the bride and groom went to inspect each other's family property.

The decisive event — the solemn consolidation of consent to marriage — was known as zaruchyny (engagements): poshliubyny, zvovyny in Volyn, slovo in Khmelnychyna, slovyny in Lvishchyna, male vesillia in Poltavshchyna, rushnyky, khustky in the central regions of Ukraine, svatannia, svatanky in Zakarpattia and southeast regions of Ukraine. The etymology of the word ‘zaruchyny’ is associated with the ritual bonding of the hands (‘ruky’) of the newlyweds on bread or grain. There is a lot of evidence, in particular from Poltavshchyna and Cherkashchyna, that the bride’s hands were tied with the elders’ ryshnyky (embroidered cloth pieces). The regional customs of this stage were ‘zatanciovuvannia vesillia’ (‘the wedding dancing’) in Volyn, Lvivshchyna, and Ivano-Frankivshchyna, as well as the first posad molodykh (seating of the newlyweds at the table), and receiving the first parental blessing. Termination of the pre-wedding agreement was an exception to the rule. In case it occurred, the girl's parents were required to reimburse za obrazu (‘for the offence’).

In the past, a rural wedding lasted from three days to a week, depending on the financial situation of the families. Friday (‘piatnistia-pochatnitsia’) was considered the most favourable weekday to begin the festivities. On this day, the female bakers baked a loaf (‘korovai’) and other wedding pastries (kalachi, shyshky, lezhen, dyven), and the bride and groom visited future guests, inviting them to the wedding (zaprosyny).