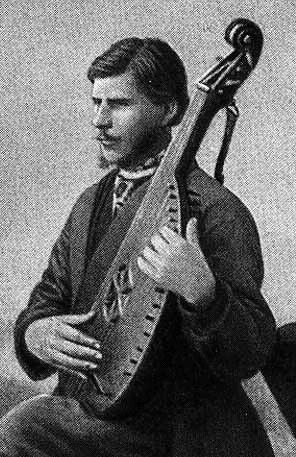

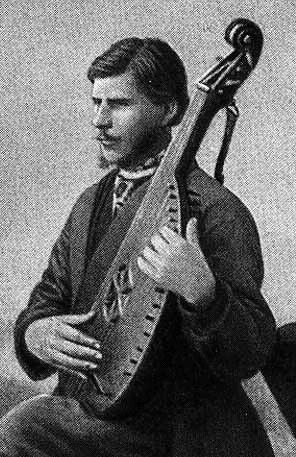

Old Postcard. Lirnyk Timish from the Outskirts of Poltava. wikipedia.org

Kobzarstvo and lirnytstvo were male occupations, and, as a rule, kobzari, lirnyky, and bandurysty were blind. They earned their living, in their own words, ‘begging’; this led to a nomadic lifestyle. While at home, they performed feasible household chores and engaged in handicrafts (mostly knitting ropes). In our contemporary terms, their main activity was artistic: they were itinerant musicians who sang to the accompaniment of a musical instrument such as the kobza, bandura, or lyre. The songs performed by kobzari differed somewhat from those performed by lirnyky, differed somewhat from between but they were united by their repertoire base: epics (dumy, historical songs), the spiritual tradition (psalms, songs of religious content), and instrumental music for dance (sometimes with refrains). It is clear that traveling musicians could often be found in crowded places such as at fairs and bazaars, near churches, on village holidays in the summer, and near the taverns. However, they were also often invited to play in wealthy homes where they could receive temporary shelter for a few days.

According to some researchers,

kobzarstvo was a regional phenomenon that was widespread in the territories of the former Hetmanate (now Poltavshchyna, Chernihivshchyna, and Sumshchyna), and in the 19th century, it spread to Kharkivshchyna and partly Kyivshchyna. According to other researchers, this musical tradition was present in Pravoberezhzhia as well but disappeared over time. In particular, there is mention of the banduryst Vasyl Varchenko from Zvenyhorodka in the records of

Haidamak units during the Koliivshchyna uprising.

Kobzars are also depicted in many of Shevchenko’s drawings and recollections from his childhood — which was spent in Pravoberezhzhia.

Lirnytstvo was widespread in all areas, equally popular in the Slobidshchyna, throughout Polissya, Volyn, Podillia, and the Carpathian regions.

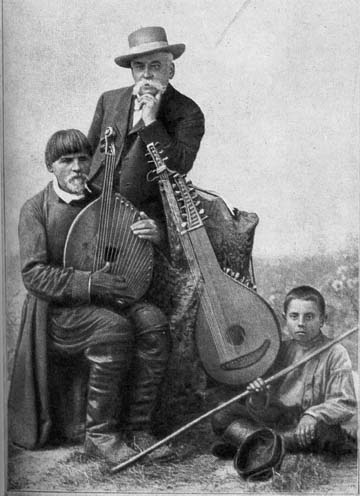

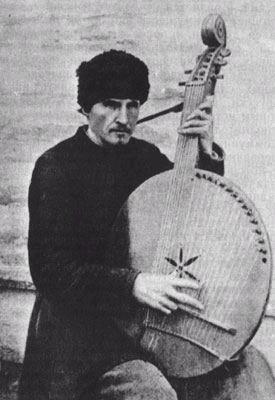

Kobzar, Ivan Kuchuhura-Kucherenko. 1902. wikimedia.org

Kobzar-lirnyk art of the 19th century was of a folk professional calibre: kobzari and lirnyky formed workshops (‘fellowships’). One initially practised as a student for many years. This began in childhood when a blind boy or young man became an apprentice to the panotets (father) who taught him to play instruments and sing over at least three years. There were exceptions to this rule: Ostap Veresai's education lasted only a few months. The panotets employed a particular method to teach students how to play a musical instrument. Most often, the panotets taught by laying his hands on the hands of the student; he recited the work ahead of time for the student to memorise. There were other methods too. For example, the priest would order a student to pluck a certain string. Lirnyk Hrytsko Oblichenko recalled that ‘his teacher taught him by tying his fingers. He taught me to sing by singing, not by reciting ahead.’

Kobzar, Ivan Kuchuhura-Kucherenko. 1922. wikimedia.org

After completing his studies with the panotets, the young kobzar had the right to apply for membership to the workshop. To do this, one had to pass an exam and go through a ritual called odklinshchyna at the fellowship: it was necessary to bow to the brethren and receive a blessing from them in order to join the professional society. After passing examinations,he received ‘vyzvilka’— therelease from the teacher’s care, making him eligible for independent craft and earnings in the form of startsiuvannia and kobzariuvannia. It was also necessary to earn the right to be a master, a panotets, and to teach students as apprentices. The rite of odklinshchyna is a typical professional initiation rite. Its obligatory elements included examinations for professional suitability (knowledge of the repertoire and fellowship laws, performing skills), ceremonial feasting, and giving gifts to panotsy. After passing this rite, the apprentice was called ‘odklonennyi’ (‘bowed’), and ‘vyzvolenyi’ (‘liberated’). He became a master and received the right to engage startsivstvo in the area defined by the fellowship.

Kobzar and lirnyk workshops were organised akin to handicraft workshops. They had their own hierarchy: the professional council called sudna rada (‘judging council’) included panotsy (‘panmaistry-elders’) who formed the radna starshyna (‘council or workshop foreman’). At the head of the workshop, there was a workshop master (prapanotets). Each fellowship had its own area of business. Blind musician guides were not allowed on the workshop council.

Kobzari and lirnyky had their own secret slang (argot) — the Lebiiska language. It was ironically called ‘Kalipetske govrydannia’. The vocabulary of this language consisted of unrecognisably modified Ukrainian words as well as loanwords from modern Greek, Gypsy, Romanian, Hebrew, German, Hungarian, Turkish, Russian, and Swedish.

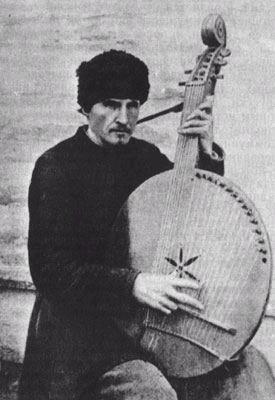

Banduryst, Terentii Parkhomenko. wikimedia.org

History has kept the names of famous folk singers of the late 19th - early 20th century: kobzari Ivan Strichka, Khvedir Hrytsenko-Kholodnyi, Ivan Kravchenko-Kriukovskyi, Ostap Veresai, Mykhailo Kravchenko, Hnat Honcharenko, Fedir Basha, Andrii Shup, Petro Kolybaba, Pavlo Bratytsia, Terentii Parkhomenko, Petro Drevchenko, Musii Kulyk, Vasyl Nazarenko; lirnyky Arkhip Nykonenko, Ivan Peresada, Mykolai Doroshenko, Stepan Pasiuga, Samson Veselyi, Nestor Kolisnyk, Varion Honchar, Anton Skoba, Nestor Boklag and others.

Petro Drevchenko. wikimedia.org

After the revolution of 1917, the situation changed drastically as there was an active effort to eliminate the kobzar-lirnyk tradition. In the 1920s and 1930s, researchers were ‘catching’ the last authentic bearers of tradition and recorded them. Kateryna Hrushevska published the corpus ‘Ukrainian Dumy’ that became a banned nationalist publication after her imprisonment and exile. Kobzari and lirnyky were forced to ‘adjust’ to socialist values, to Marxist - Leninist ideology, and compose ‘new dumy’ about Lenin and Stalin. This initiative did not gain much traction. However, the authentic artform was superseded by the concert activities of bandura bands who began to form trends and genres of Ukrainian singing and instrumentation.

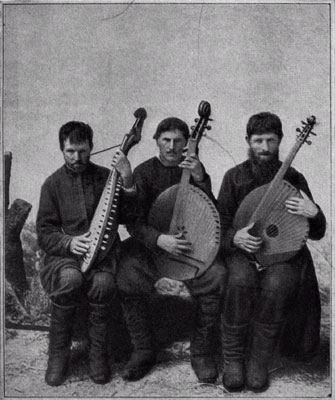

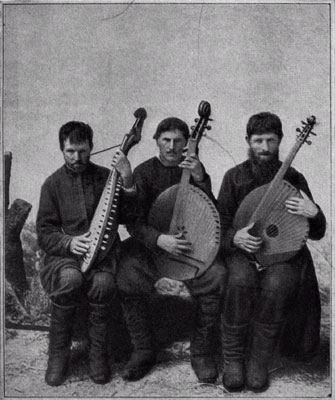

Kobzari: Mykhailo Kravchenko, Tereshko Parkhomenko, and Petro Drevchenko. wikimedia.org

There are only rare cases where the authentic tradition has been preserved thanks to such performers as banduryst Yehor Movchan, lirnyk Ovram Hrebin and others.

A new historical stage of the kobzar-lirnyk tradition is associated with the Khrushchev Thaw of the 1960s. First, there were attempts to adapt traditional performance styles and repertoire to the emerging conditions of big cities and an increasingly urban society. Ukrainian intellectuals were bearers of a new national idea that was taking shape in private underground rooms and began to shape the artistic environment.

The

banduryst Hryhorii Tkachenko, a student of Petro Drevchenko, was instrumental to the success of the

kobzar-lirnyk tradition in this period. He gave new life to the traditional repertoire (

dumy, psalms, historical songs), he demonstrated that in the second half of the 20th century bandura may sound old - fashioned, but it has cultural value. He mentored a number of students who have been instrumental to the celebration of Ukrainian culture today. Among them, there are

Mykola Budnyk, Volodymyr Kushpet, Viktor Mishalov, and Taras Kompanichenko.

Kobzar Mykola Budnyk. wikimedia.org

In the present, we have witnessed the revival of the kobzar-lirnyk tradition and the introduction of its rich heritage to modern culture. Contemporary Ukrainian kobzari and lirnyky have created a demand for traditional repertoire, made this art form an integral part of modern culture, and combined performance with some related activities. This is exemplified by efforts to search archives for musical manuscripts of the Middle Ages, Renaissance, Baroque, and Classical periods and incorporate them into the repertoire (Taras Kompanichenko), open workshops to teach students how to play musical instruments (Taras Yurii Fedynskyi) create ensembles that mix bandura, kobza, and basolia with ancient instruments (‘Khoreia Kozatska’ band), and the revival of lirnytstvo (Mykhailo Khai). An interesting phenomenon has emerged when singers leave the concert halls and go ‘into the street’, becoming symbolic of freedom heralds (for example, the important role of kobzari and bandurysty in the Maidan events).

Taras Kompanichenko. wikimedia.org

Kobzari are also trying to revive traditional social forms of community, in particular, gathering in workshops (Kharkiv Kobzar Workshop, Kyiv Kobzar Workshop). The centres of traditional kobzariuvannia are now Kyiv, Kharkiv, Lviv, and Lutsk. Kobzar workshops try to teach epics to the blind, hold annual scientific and practical conferences ‘Kobzar-lirnyk epic tradition’, publish collections of materials, organise an annual festival of epic tradition called Kobzarska Triitsa, concerts, organize kobzariuvannia sessions in the Ivan Honchar Museum, organize the Kobzar-lirnyk Pokrova festival, and also a number of festivals and events in other cities and villages of Ukraine, such as Lira-Fest, Kobzar camp in Kryachkivka).