Link copied

December 06, 2021

How notions of biological age have changed

Throughout society’s cultural evolution, notions of biological age have undergone significant changes. According to contemporary scientific understandings, which more or less correlate with a basic understanding of biological time, each person’s life goes through the following periods: childhood, youth, adulthood, and old age. According to the World Health Organization’s classification system, people aged 60–74 are considered elderly, those 75–89 are considered in their senile age, and anyone 90 and over is a “long-lifer”. Sociologists call these periods of human life the “third age,” while demographers use the concepts of “third” (60–75 years) and “fourth” (over 75) ages.

The traditional Ukrainian understanding of aging and the period called “old age” differs from our contemporary understanding. Studying the linguistic and ethnocultural particularities of Ukrainians allows one to identify traditional notions about old age and determine what role people in this category played in traditional culture. The most widespread vernacular terms for elderly people are did (loosely “grandpa”), baba (loosely “grandma”), and elder. The polysemy of the words did and baba points to the importance of these figures in Ukrainian folk culture. These concepts concern both living people and the cult of ancestors. For example, did can mean: ancestor; sage; patriarch; senior in the family; mother’s or father’s father; old man; deceased; elder; poor man; beggar; primogenitor; spirit of ancestors; etc. The main meanings of the word baba are old woman, mother of father or mother; a woman who delivers babies; witch or soothsayer; matriarch, protector, defender, keeper of the family hearth, and so on.

The concepts of baba and did permeate ritual, social-the everyday, and mythological spheres of life. The words are often contrasted or presented in pairs to emphasize the unity of female and male essences. For example, the hay that is spread under the Christmas dinner on Christmas Eve is the did, and the straw that sits in the corner where the grandfather-sheaf is placed on Christmas Eve night is the baba. The ancient village dish composed of flour and millet (a type of lemishka) is called did, while the sweet bread (a pastry of wheat flour, or paska) is baba. Furthermore, Did and baba are names for parts of the krosna (a hand loom); these names are given to children’s games and toys; the last sheaf of wheat in Ukrainian harvest rituals, scarecrows set out in the garden or field, and so on.

The word staryi (“old”), is a derivative of the root stā - r(о)- —“great”— and indicates a person’s age: someone “great” that is “grown.” Folk proverbs and sayings reveal particularities in the understanding of old age as a transitional state. This is highlighted by contrasting old age with youth: “Look for truth in the old, and strength in the young”; “If youth only knew and old age only could.” Old age demands respect; an integral value and ethical norm of behavior for Ukrainians: “Respect the old, for you’ll be old too”; “Honor the old and the young will honor you”. Opposite connotations are also often associated with old age: the positive traits are wisdom and experience (“Reason comes with age,” “Listen to old people: you’ll gain others’ wisdom and keep your own, too”), while the negative traits are weakness or feeblemindedness (“The old man knows a lot, yet forgets even more”, “The old man’s head is like the rest of him: there was a lot and it’s all gone with the wind”, “What is old, what is small, is dumb”).

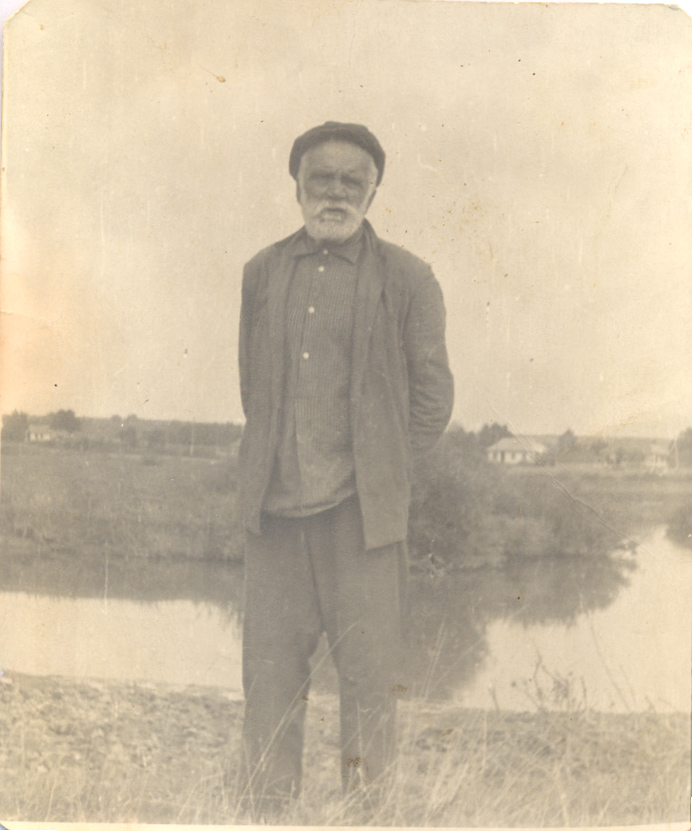

In traditional society, the concept of old age had both a biological (reproductive) and social dimension. Old age was considered the period in life when physical activity is lessened, there are outward signs of aging, and one’s health worsens, among other experiences. Old age was not defined by objective characteristics (number of years lived), and there was no clear age hierarchy or corresponding rites of passage. Generally, the acquisition of the status “old” was accompanied by the cessation of certain social functions, the transmission of sacred knowledge, and the acquisition of a new and special role in society. Socio-demographic changes, in common understanding, happened between ages 45 and 50 (rarely 60). Since the majority of girls married between 16 and 18 and boys around 20, at 40–45 they would have already had their first grandchildren and had become grandpas and grandmas. Ukrainians considered this age to be old age: “Pigs are walking ‘round the field, // And an old grandpa is following them // He’s already 40 years old”, “An old grandpa got married // he found himself a grandma of forty years”.

Notions of old age in traditional culture

Old age correlated to social factors and the body’s biological cycle which were viewed in the context of prohibitions, orders, and sanctions symbolic in nature. These mostly concern women, and men to a lesser degree. Physiological changes in women’s bodies were, among others, the main criteria that made women babas. It was with the loss of the ability to bear children that a woman transitioned to the status of baba. This transition to a “clean” state with the onset of menopause gave women new opportunities: 1) to become a baba-midwife/baba-cadet; 2) to practice witchcraft healing (men had no hard age limits for practicing folk medicine); 3) to carry out moral censorship and, if needed, even check a girl for virginity; 4) to take part in burial rituals (washing the deceased, reciting prayers). Simultaneously, according to folk beliefs, participation in burial rituals ruled out helping with deliveries so as not to harm the newborn.

In this system of archaic beliefs, old age appears as a liminal state of human existence in which old men and women were given the status of baba and did, which ostensibly made them mediators between this and the other world.

The status of baba or did also imposed certain prohibitions regarding marital life, in particular the cessation of sexual relations. For dids and babas, sleeping together was considered shameful. Intimate relations were considered no longer necessary, which attests to a view of sexual activity as primarily a reproductive function.

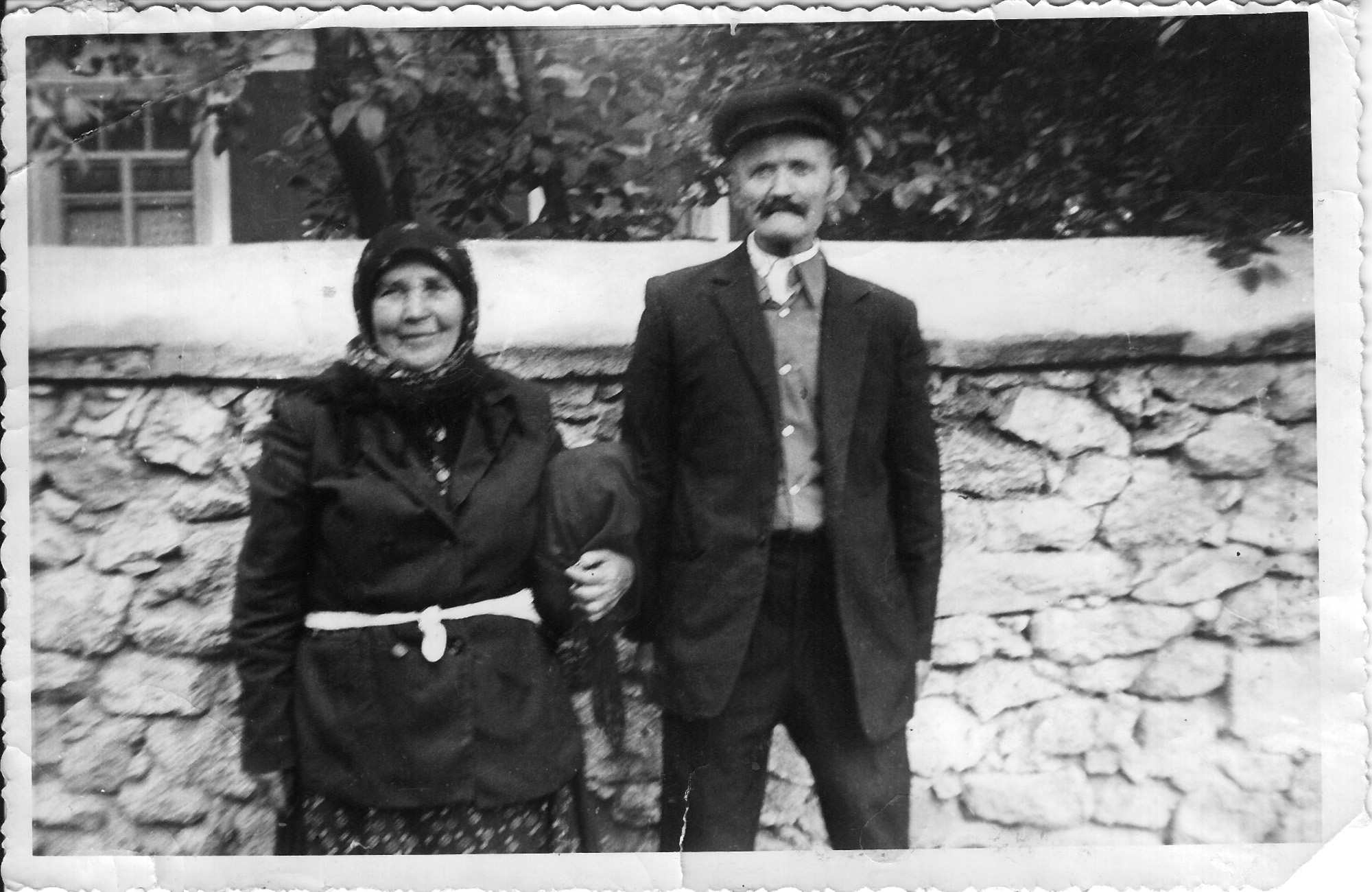

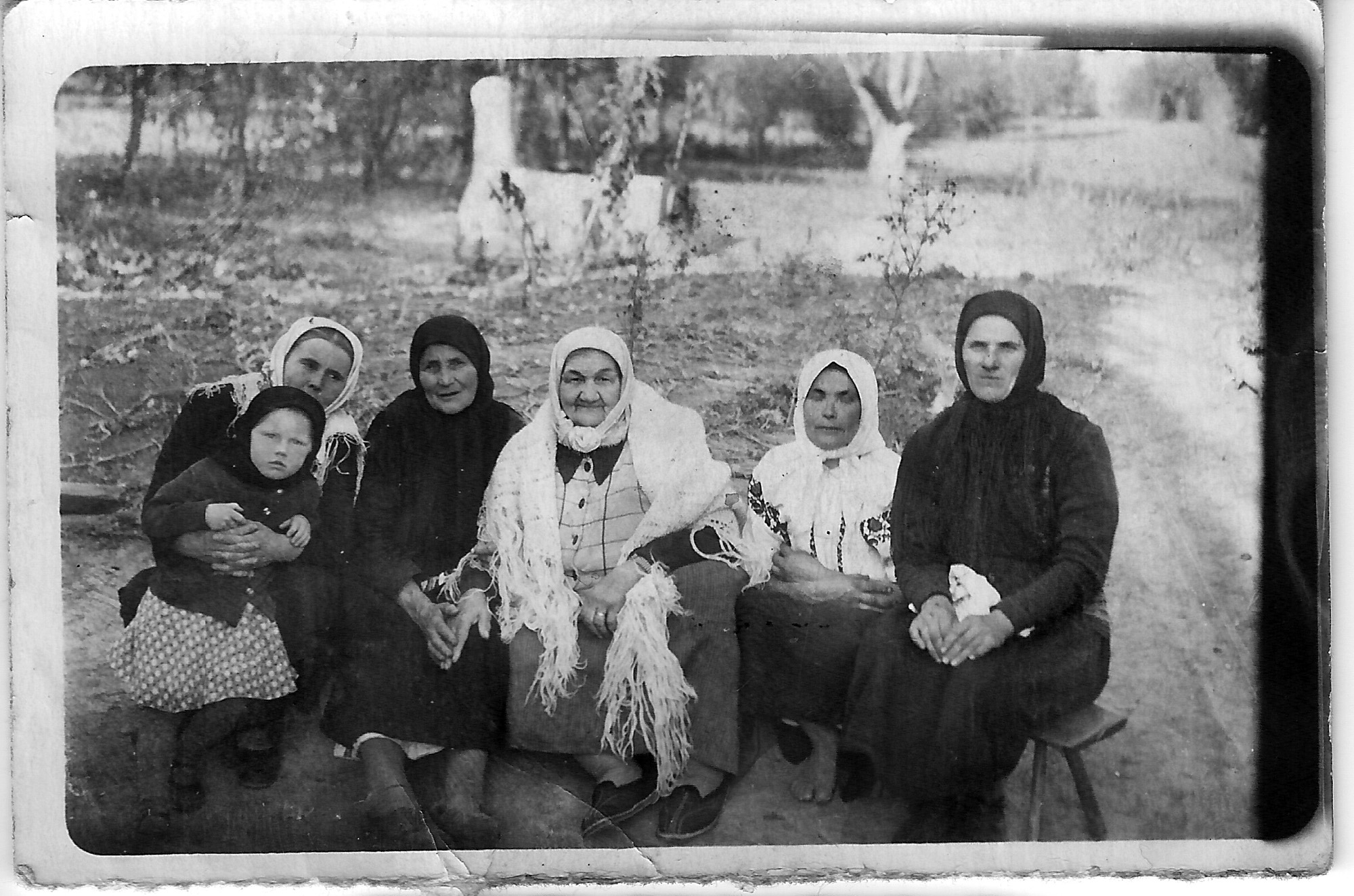

The material culture of elderly people, in particular the features of traditional clothes, hairstyles, and headdresses, held symbolic meaning corresponding to a person’s age. Clothing and shirts were sewn from dark colored fabrics and had only minimal embroidery or lacked it entirely. Old women often cut their hair short and in all cases covered their heads. In Podilia, for example, a special way of tying head scarves was developed for old women: the ends came up under the chin and were twisted around the head (above the forehead) without being tied while the fringe hung down. Scarves were worn over hoods from underneath which a white kerchief peeked out. This type of headdress was called a baba.

As for living arrangements, older people lived out their lives in the families of their children (daughters, sons, sons-in-law, daughters-in-law). It was babas and dids who took main responsibility for teaching and raising their grandchildren, familiarizing them with folklore and family, and annual customs. In carrying out the domestic work they could manage,, they instilled the skills and knowledge of work in the children.

In daily life, old people communicated actively among themselves, gathering every evening on benches on the street, during church services, while observing annual ritual holidays, family celebrations (weddings, funerals), or civic events. A lack of communication with peers, illness, the sometimes bad attitude of children (the saying “We have three woes: death, old age, and bad kids” attests to this) made them feel lonely and depressed.

In general, the elderly enjoyed rather high status in village society and in civic life. They had significant influence on the formation of ethical and behavioral norms, provided that throughout their lives they themselves fulfilled their society’s basic social functions and gender norms (this mostly concerned married women, who bore children and managed their households).

Old people prepared for their deaths well in advance, revealing a natural pragmatism: they ordered or built their own coffins and kept them in the attic; they “held a place” in the cemetery near their deceased spouse; they prepared their “death clothes,” candles, scarves, and handkerchiefs for their funeral guests. They tried to complete all important domestic tasks and get their estates in order by composing an oral or written will.

In preparing for death, the elderly, especially the infirm, were trying to take care of their spiritual selves in order to leave this world with clear consciences. The Christian rites of confession, eucharist, and anointing, as performed by a priest, played a significant role in this. It was the elderly, their children, and the priests who made sure the sacraments were carried out. These were important not only from a religious-Christian, but also popular-secular point of view. It was believed that the sacraments cleansed the soul from earthly sinfulness, eased the painful departure from earthly life, and ensured a better posthumous position, since death was traditionally conceived of not as the final ruination of the soul and body, but as a transition from one form of existence to another — the otherworldly life of ancestors.

Notions of and honoring the cult of ancestors

In traditional cultures, the cult of ancestors had special meaning. It was common to consider the soul and the spirits of ancestors as guardians of the human family, upon whom the living depended for their spiritual and material well-being. In folk beliefs, ancestors were endowed with supernatural powers: they protected the territory, livestock, crops, and people themselves from earthly enemies and the criminal plans of evil forces, interfered to provide favorable weather for the future harvest and fertility of the land, and ensured the health of the living and their year-round well-being. In return, their relatives in this world organized ceremonial appeasements, communicating with the deceased in the form of regular offerings of sacrificial food (the main funereal dish was kolyvo, a sweet porridge made from wheat berries) and drink. The dead are remembered in spring, summer, fall, and winter on days of the dead: after Easter these are Mohylky, Didy, Hrobky, Provody; on Pentecost and Navsky Easter (Easter of the Dead), Rusaliï, for Saint Demetrius’s, Saints Cosmas and Damian’s, and Saint Michael’s feasts, the Didivski Saturdays; as well as during religious and family holidays (the dead were invoked when the korovai was cut at a wedding; gifts were given to older people “for the deceased”; holidays such as Christmas Eve, Christmas, the Apple Feast of the Savior [Feast of the Transfiguration], and parish feasts, among others).

The cult of ancestors — the most archaic of Ukrainian rituals present in contemporary customs — manifests itself by preserving the memory of close, deceased relatives, honoring the dead, and visiting and looking after their graves.