Link copied

December 10, 2021

Today, researchers and collectors tend to understand naїve art as the art style of self-taught countryside artisans — artists without special education. Petro Honchar's metaphorical term ‘pure art’ emphasises the art form’s independence and the fact that the creators themselves were not limited to drawing skills. There are a wide range of terms to denote this and similar phenomena: naive, primitive, art brut, folk painting, amateur art, and kitsch.

The history of the term art naif (naїve art) dates back to the Paris exhibition Un siecle de peinture naive of 1933 where it appeared in the exhibition’s very title. Oto Bihalji-Merin, the researcher, collector, and compiler of The World Encyclopedia of Naive Art — he most important publication on this subject — , lists naїve art’s key features. These include its independence from professionals, an instinctive nature, and an explicit individual creative style marked by a fresh and joyful perception of the surrounding world. This encyclopedia features the names of some Ukrainian artists from the USSR: Maria Buriak, Oleksandr Vyshnyk, Olena Volkova, Ivan Lysenko, Elyzaveta Myronova, Maria Prymachenko, and Ivan Cherniakhovskyi.

Folk artists — having no special art education — borrowed images from the world around them that reflected certain archetypes, and then reproduced them. As time passes artists, techniques, and the environment changes, but some things remain the same. Modern tire swans that decorate yards in Kyiv and other cities are nothing more than the swans from idealistic landscapes that hung in country homes throughout the 20th century.

Serhii Makovskyi wrote in 1925 “Indeed, folk art is as far away from vulgarity as possible. It fascinates with its nobility of shades and diversity in its canonical ossification. […] It combines collective skill with the uniqueness of original works, [it] is not individualised, in our urban understanding, and at the same time is marked by a personal accent. The most enduring rural ‘cliches’ do not exclude well-known artistic freedom. On the contrary, it is from freedom that unique beauty is born. The same thing, but a little different every time. Folk art […] is thrilling, with barely perceptible differences yet without becoming a handicraft copy, without degenerating into a soulless product: the craft remains an art”.

According to researcher Ksenia Bohemska, the creation of images that depict a happy life often involve the auto-therapeutic practice of supporting oneself as a person. If you trace the fates of many famous naїve artists, you will find that most of them turned to drawing and painting while attempting to overcome severe stress, emotional distress, illness, separation, or the death of a loved one. In Bohemska’s interpretation, the joyful spirit of the paintings function as compensation for hard experiences. In particular, two stars of Ukrainian naїve art, Kateryna Bilokur and Maria Prymachenko, were seriously ill throughout their lives.

The concept of naїve art is more narrowly defined than folk art. Naїve art is often created by an identified artist, while folk art is produced anonymously. Folk paintings (or folk pictures) are closely connected with naїve art. They were created to entertain children, decorate homes, or to be given as gifts to relatives. They were purposely painted for sale at marketplaces as so-called market kitsch. According to researchers, the folk picture is emblematic of the principle of kitsch, but rural kitsch fell into the sphere of folk culture and was combined with tradition.

In their work, masters who produced folk pictures used various techniques, materials, and surfaces to create the image. Folk art also appears in such marginal mediums as, for example, woodcarving.

According to experts, Ukrainian folk painting began to develop in the 18th century. The most common image within the field ofUkrainian folk painting is ‘Kozak Mamai’. The painting depicts a Cossack sitting cross-legged (sometimes described as ‘Buddha pose’), with a horse, tree, pipe, and other accessories next to him.

In the 20th century, popular subjects for folk pictures included ‘The Cossack and the Girl’, ‘As the Cossack leaves, the little girl cries’, and ‘Petro and Natalka’. They are depicted in a pastoral light. The pictures often included landscapes, which were sometimes even exotic (for example, with palm trees). Images of people (for example, girls sailing in a boat or sitting by the river) are depicted in silhouette. It was common to paint portraits of family members, friends, neighbours, as well as countryside estates, households, and household activities. Folk painters also frequently created still lifes, the most common images featured a watermelon and flowers. Illustrations of folk legends, songs, fairy tales, and historical events are also popular subjects. Some compositions are copies of famous paintings that folk painters saw in books as reproductions.

Sometimes, it is very difficult to find the original source of a subject. For example, Ukrainian naїve researchers agree that the painting Olenka with a deer (the image of a girl next to a deer with flowers) could have originated from a chocolate or soap (shampoo) wrapper.

However, the composition Angel guards the children is of Western European origin. At the beginning of the 20th century, leaflets with this religious subject were widely circulated in Europe.

In general, the key compositional features of folk pictures are symmetry, ornamentation, and a planar-decorative nature.

In 1915-1919, Ukrainian-French avant-garde artist Aleksandra Ekster—who was friends with the French artists Fernand Léger and Pablo Picasso—was reviving Ukrainian folk crafts. She discovered and inspired a group of artists (Hanna Sobachko, Ievmen Pshechenko, and Vasyl Dovhoshyia) whose artwork was called folk futurism. During Labour Day celebrations on May, 1st 1919, Khreshchatyk Street was decorated with the works of folk artists. In the Palace of Arts (now the National Philharmonic) at the Exhibition of Contemporary Farmer Art, the art of Hanna Sobachko was exhibited — a decorative panel made of paper that imitated a traditional carpet.

Ukrainian folk art of the early 20th century had a significant influence on avant - garde artists, in particular, Kazimir Malevich, David Burliuk, Aleksandra Ekster, and other world renowned painters. They often ‘borrowed’ shapes, colours, and subjects from folk artists.

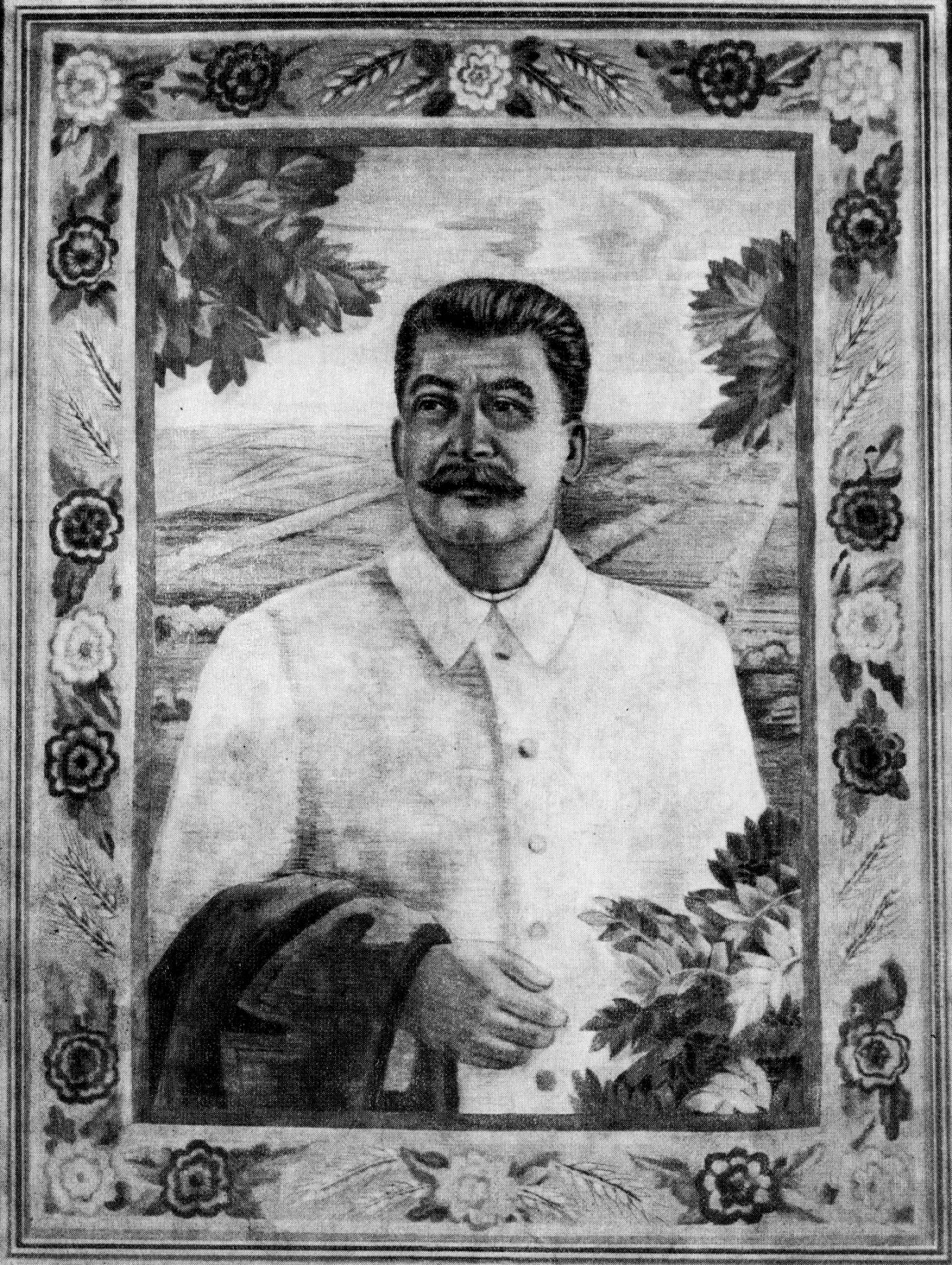

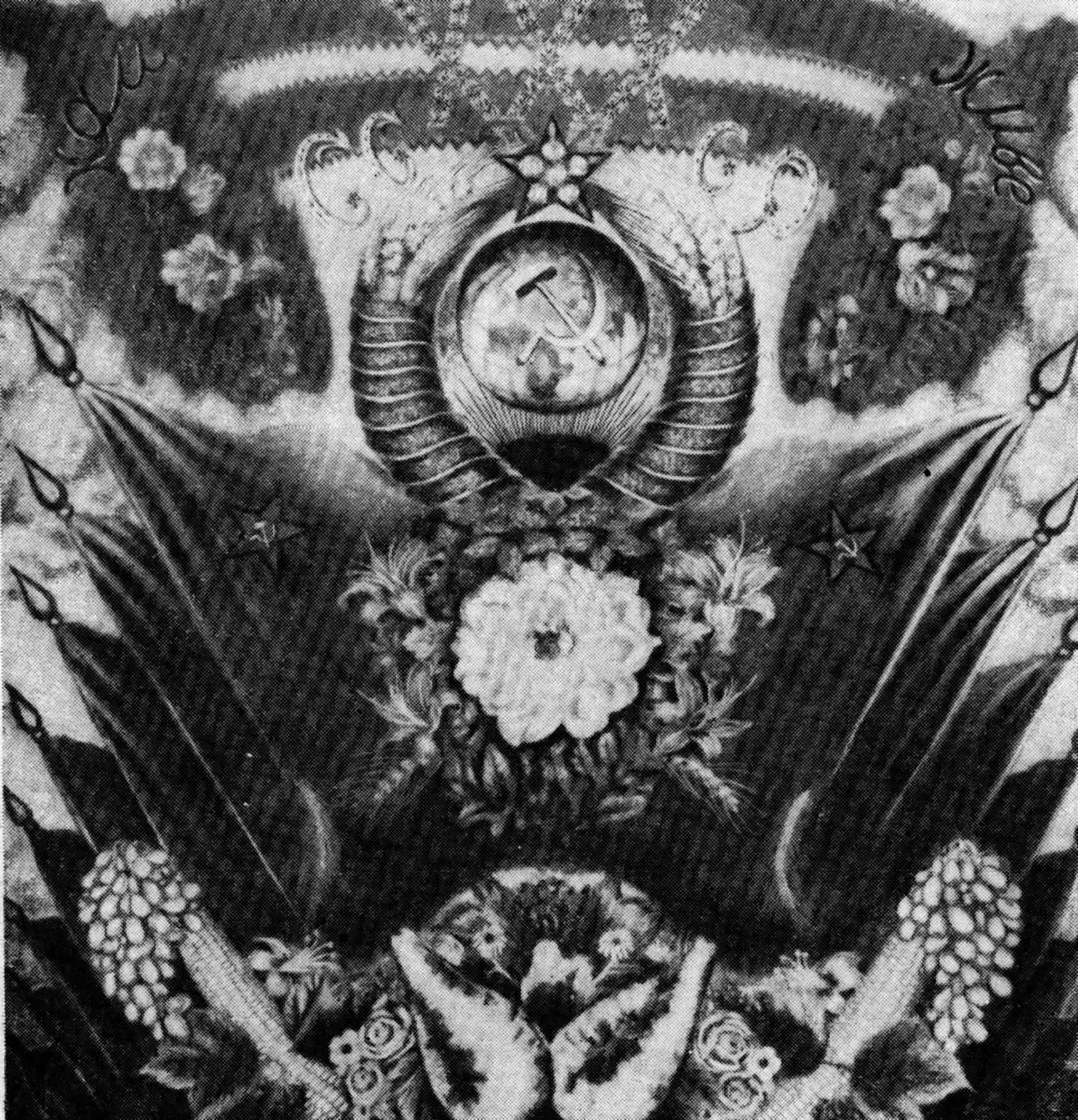

Soviet authorities often massacred or silenced professional artists; however, naїve art was treated with respect. The best illustration of naїve art from the 1930-50s era are luxurious carpets featuring Stalin’s portrait framed by traditional Ukrainian ornamentation.

In the 20th century, images emblematic of folk painting were replicated in various techniques and mediums. Photography provided new forms of replication. Thus, from the second half of the 20th century, oval pictures featuring well-known subjects became popular, and black-and-white images were coloured by hand. It is known that postcards were also created using this technique.

In Soviet times, naїve art was considered anonymous. It was believed that folk art, like the people themselves, was a mass phenomenon without any individuality. For instance, the book ‘Decorative and Applied Art of the Ukrainian SSR’ (based on the 1949 exhibition materials) reproduces two outstanding works by Kateryna Bilokur, namely Tsar Kolos and 30 years of the USSR, but does not indicate their authorship.

The phenomenon of naїve art takes new forms nowadays. Many professional artists have turned to the naїve style. Oto Bihalji-Merin wrote that in the modern world, folk art is becoming obsolete as the collective art that is its foundation is falling apart. Instead, it is throwing from its bowels independent individuals: naїve artists. Today, naїve art is not limited to the farming environment and countryside bazaars but has become an integral part of urban culture. In addition, its subject and function have expanded, manifesting not only in paintings but also in sculpture, music, words, and even in the art of acting.