Link copied

December 06, 2021

In a patriarchal society, principles of demographic division were not based on the premise of gender, as today, but first and foremost, on biology and the reproductive cycle; therefore, social factors were governed by it. Today the upper parameter of “youth” is considered on average around age 35 regardless of a young person’s marital status. In agrarian pre-industrial societies, the period of “youth” centered around marriage and procreation with young people marrying around age 16-20. The lower parameter of what was considered youth coincided with adolescence; however, in the past, adolescence began later than it does today. The scientific term to denote this age group includes note of marital status – “unmarried youths”.

The folk terms to denote people of this age group are bachelor (“parubok” in Ukrainian, derived from “a young worker”; a male who can work efficiently according to his physical abilities) and maiden (“divka” in Ukrainian, derived from the notion of “a female that is able to breastfeed”; a young female of reproductive age). From these two nouns derive the denominatives and derived verbs–bach/remain unmarried; bachelorhood/maidenhood.

At this age, a person was already able to participate in work activities that required physical abilities and practical skills. For example, scything, harvest work, threshing, hoeing; woodwork – chopping, sawing, joinery, housebuilding; cattle pasturing; cooking in the oven and handling the oven prongs and pots; handling a spinning-wheel, a needle, a smoother; washing in a washtub and using a water butt for bucking, among others.

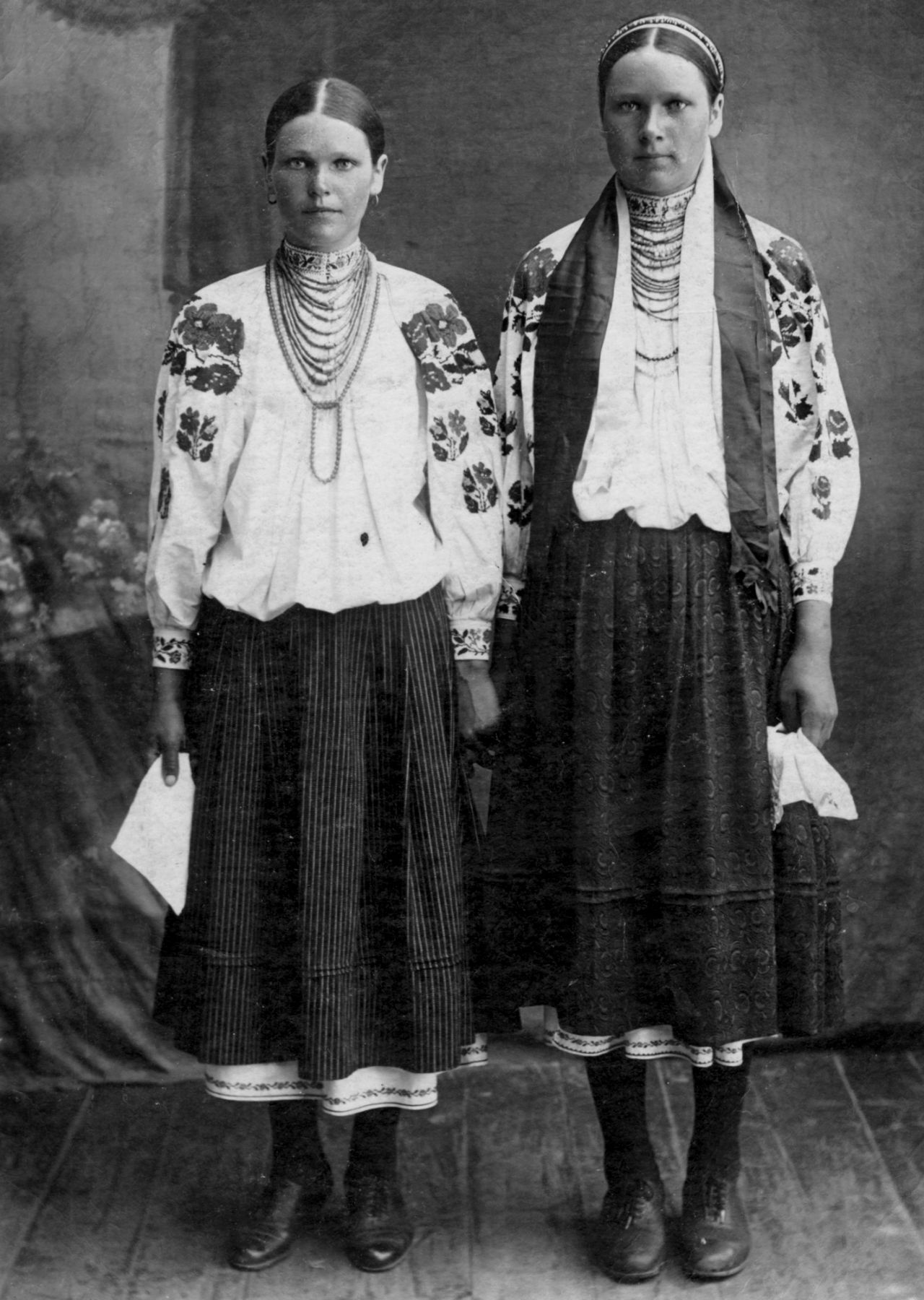

How members of the age group dressed also changed at this time (compared to the previous age group–children). It manifested (first and foremost when it came to girls) in additional garments for festive and special occasions, a more sophisticated silhouette, as well as decorations for everyday outfits. The outward appearance of young unmarried girls differentiated them from married women; this included such markers as hair style and head coverings. Girls did not cover their heads in warm seasons, tied their hair into braids, and on high days (on Sundays) decorated it with a band (ribbon). During certain festive rites (for example, a wedding), unmarried women wore a wreath (flower crown) on their heads.

In patriarchal societies, this short stage of life was rather eventful and was bound with the early marriage traditions (for some individuals, especially females, it lasted only for 3-5 years)l. Within this period, the process that can be tentatively called gender self-identification occurred: young people became well aware of themselves as representatives of a certain sex group and could imagine themselves as future marriage partners. For this reason, communication between the two sexes was the predominant theme during adolescence and youth. In Ukrainian ethnic studies, the term pre-marriage communication of the youth is used.

Beyond rituals, communication of young people looked as follows: during warm seasons of the year when there were no intensive agricultural activities to perform, mixed groups of maidens and bachelors gathered in the evenings in every neighborhood (street). Singing “contests” between different neighborhoods took place accompanied by dancing and telling jokes. During cold autumn evenings (before the wedding period), young people gathered in a room (a rented house) for evening company and overnight get-togethers. Girls often arrived earlier and kept busy spinning, embroidering, and singing. The situation warmed up after the boys arrived. They played cards, made fun of the girls, and flirted with them (“teased them”). There was a local custom fixed in ethnographic literature where the girls and boys cuddled overnight without physical intimacy.

In this period, parents chose their children’s marriage partners and strict boundaries existed for communication between the sexes. Certain models of communication allowed unmarried youth to practise skills necessary for future wedlock (in the form of games).

The philosophy of life in traditional society valued not only the biological reproduction of society alone but also its constant recovery as a social organism. From this perspective, the bachelors’ community was “a dress-rehearsal” for adult life — a simplified model of a young person’s future participation in village community life as married men and heads of households. The bachelors’ community had a leader and its structure displayed hierarchic features; however, unlike in the village community, this hierarchy manifested itself as a the subordinate position of new members (juniors) against “experienced ones” (seniors) rather than the subordination of the less well-to-do against the wealthy. Joining the bachelors’ community was often ritualistic in nature and corresponded with initiations: ritual actions such as tests (physical and moral), initiation fees as a buy-out of one's position in a community or the right to become its member, among others.

The bachelors’ communities were in charge of maintaining structures in common countryside spaces (at the instruction of seniors including the village community or upon their own initiative). Their members also used to solve customary and legal problems inside their age group, in particular, they disciplined the abuse of moral principles, and inappropriate behavior.

In some regions, particularly in Western Ukraine, youth communities were created under the reign of churches. Their main function was to help the priest and the church fraternity and sorority efficiently practise church life. Young people performed acolytes’ duties during the divine liturgy, cleaned up, made repairs, decorated the church for the religious holidays, raised funds while Christmas caroling “for the church”, among other duties.

Calendar ceremonialism dominated the activities of bachelors’ and maidens’ groups. Married and senior individuals’ participation in village rituals was restricted mainly to interior spaces (a house, a courtyard, a homestead, a church, a churchyard, a graveyard). In contrast, young people maintained ritual practices in the “outer space” (street, neighborhood, village, and also outside the settlement – “in nature”). Bachelors and maidens were considered the communicative (“blood-vascular”) system that with the help of ritual rounds, and processions (trains) united small (familial) ritual segments into one village-wide ritual space.

It is common knowledge that there are two main culmination points on the church calendar: ChristmasThree Feasts, and Easter/the Easter cycle including Holy Trinity Sunday. However, in the folk calendar, innate ritual practices were also associated with these key events. These practices could officially, quasi-officially, or through games have a connection with church ritualis. The maidens/bachelors group was involved in the organization of ritual activities that took place outside the church. Moreover, preparation for the main events (creating ritual symbols and settings, practising songs and spectacles) was as important as their realization itself because of its role in socializing.

The winter cycle of the folk calendar included such events as fortune telling on the feast of Saint Catherine, kalyta and ritual mischief on the feast of Saint Andrew, going from house to house Christmas caroling, singing Season’s Greetings songs as well as games and the performance of “Goat” and “Malanka” spectacles. 19. “Ніч на Івана Купала”

The spring and summer cycle of the folk calendar was very rich in work activities but it included one ritual event that folklorists have connected symbolically to ancient ritual sacrifice. It included the following stages: 1) making a ritual symbol, typically in the likeness of a girl (Marena, Kupaiilo, “pole”, “poplar”) or disguising a girl who will play a role in the ritual as “an undine” or “a bush”; 2) a ritual procession around the village while carrying this symbolic figure, later to be accompanied by a worshipping play; 3) a ritual play where the ritual symbol was destroyed (physical or symbolic), accompanied by fun and games, mischiefs, and amusements. The events “Ivan Kupaiilo”, “trotting an undine round”, “trotting a bush round”, “a pole”, “a poplar”, among others, are representative of these rituals.

The maidens’/bachelors’ community was also involved in family ritualis, first and foremost, in the wedding ceremony. Maidens and bachelors were involved in every stage of the ritual from the very first moment a girl or a boy became a bride and a bridegroom, respectively, to the moment when they became married/wedded (church wedding ceremony, seating of a bride and a bridegroom). Performers were elected to fulfill the ritual roles of a maid of honor (bridesmaid), a groomsman, and the best man. They accompanied ritual action such as a bid to a wedding, bachelorette party, church wedding ceremony, trading/dowry of a bride, “wedding bread (“korovaii”) dancing, Monday “visiting”, among others.

On rare occasions, young people participated in funerary traditions, for example, ethnographers have documented boys’ participation in the funerary rite lubok game (woodcut game).

The maiden-bachelor community played a significant role in the reproduction, maintenance, and creation of folklore. In particular, they achieved this through singing several folk songs such as songs of the calendar rituals, lyrical songs, songs about love, or maiden’s/bachelor’s songs, ballads; dancing folk dances (round dances, functional dances, metelytsia ‘snowstorm’), kozachok, polka, hopak, kolomyiika), as well as performing theatrical/play compositions (“Goat”, “Malanka”, “Vertep” ,Christmas crèche).