Link copied

December 08, 2021

There is a stereotype that singing is a significant characteristic of Ukrainian people. There is some truth in this, especially when you look at the recent history of the Ukrainian folk singing tradition. The memory of ‘the whole village singing’ in the warm seasons is engraved in the memory of elderly people: the voices of singing bands were heard from different parts of the village, and each corner tried to sing over the other.

For a long time in the social sciences, folk songs were studied outside the context of everyday life. Moreover, they were studied individually within various disciplines: the musicality was studied by ethnomusicologists and the lyrics by philologists and linguists. Today, the approach has changed: songs are studied within the context of folk culture.

The records of the 19th and 20th centuries contain the most information about folk songs. The first folklorists established the general principle of categorizing songs into two main groups: ritual and non-ritual.

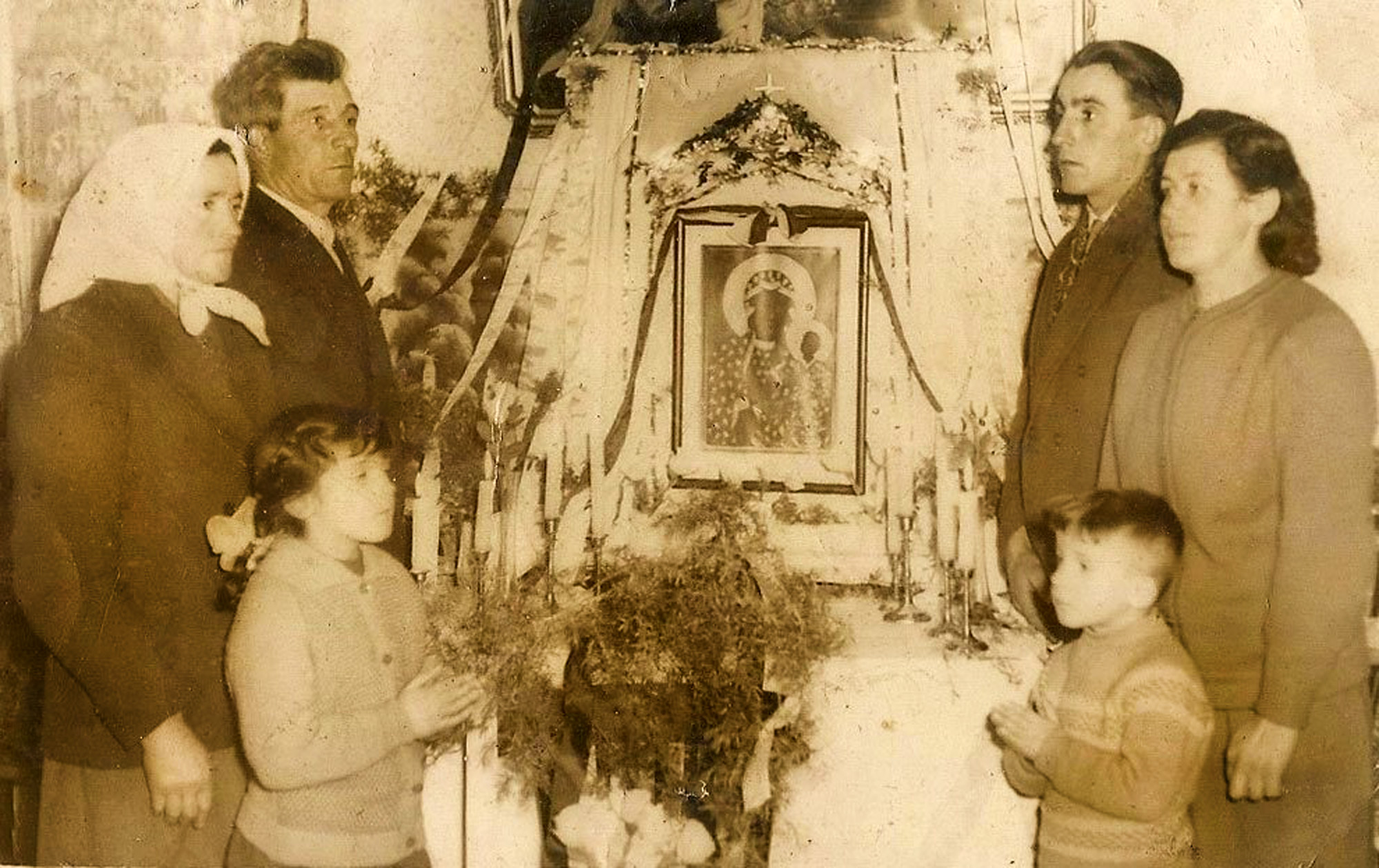

Ritual songs are considered to be the oldest due to the preservation of archaic features in the language, melody, rhythm, and poetics. Each song was performed exclusively in the context of a certain rite or ritual action. It was often only performed once a year or for several days of the year (if it concerned a calendrical ceremony), or only during a solemn family event (baptism, wedding, funeral). Ritual songs are more narrowly classified according to their function: calendar-ritual and family-ritual.

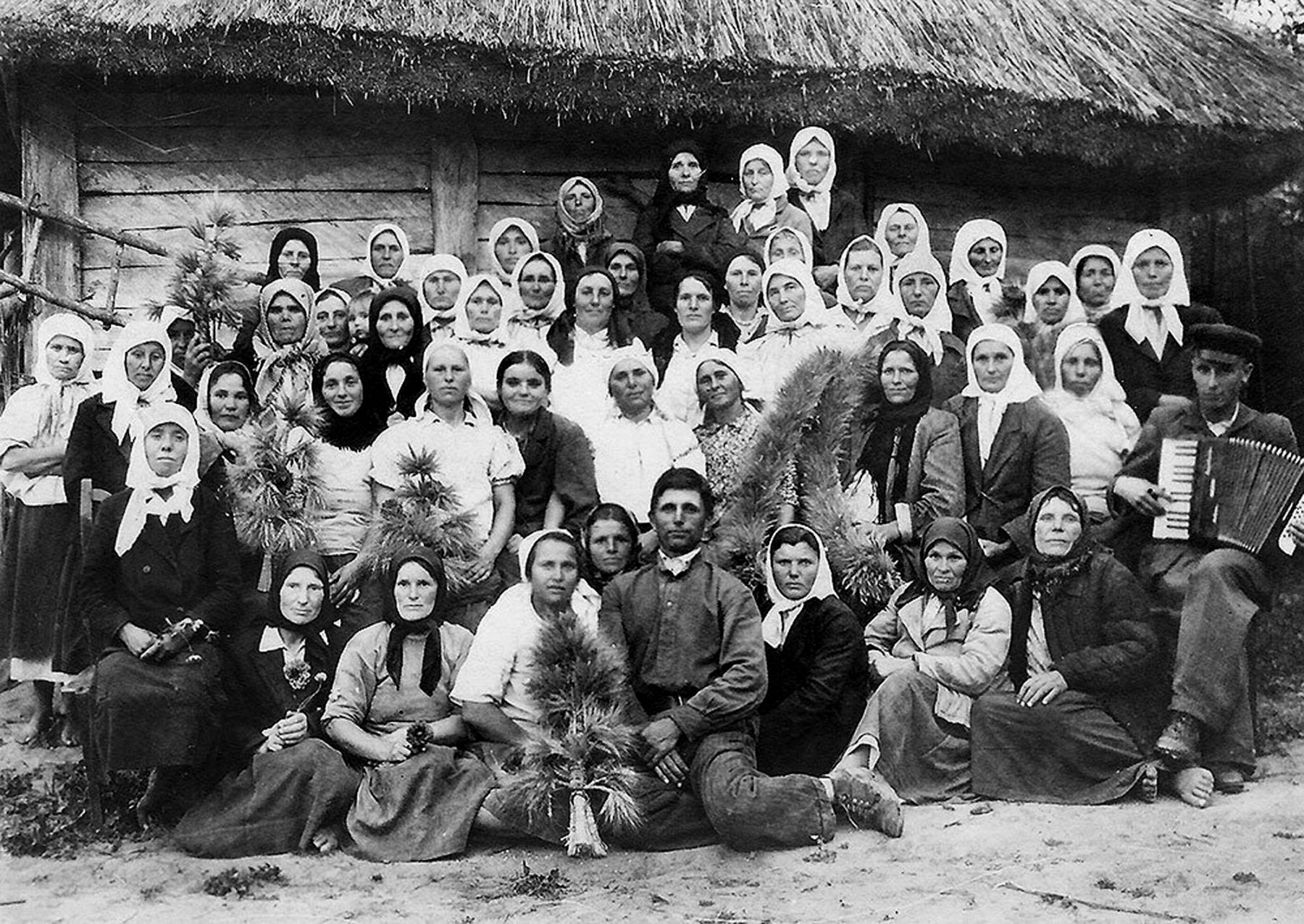

Calendar rites of the summer cycle were considered completed at harvest: zazhynky, zhnyva and obzhynky. Songs of this calendrical period were performed mainly by women's groups or individual singers, usually in between work, or on the road to or from the field. This is why some researchers attribute both zhnyvni (‘harvest songs’) and kosarski (‘mowing songs’) songs with labour songs. The song patterns are related to humorous songs and dance choruses because the most popular motive for these songs was to ridicule lazy mowers or reapers. Most of the harvest songs were obzhynkovi and accompanied rituals that took place in the field and in the landowner’s house. These songs were sung to express gratitude to the field for a bountiful harvest, to glorify the master and mistress of the household and the obzhynkova boroda (‘harvest beard’), and were sung while weaving wreaths.

The set of wedding songs is the broadest. Groups of women from both sides of the newlyweds were the main singers and event organisers. As a rule, the head of each group was either a senior matchmaker or the best singer of wedding songs in the village.

The family-ritual cycle is completed by several varieties of songs for funerary rites. These were 1) songs sung by elderly people about waiting for death and were also sung by the close circle of people directly near the deceased; 2) folk holosinnia (‘lamentations’) also known as prychytannia (‘wailing’), plachi (‘cries’), tuzhinnia (‘mourning’), and ioikannia (‘sighing’) which were performed at the funeral by close relatives or professional mourners.

Non-ritual songs make up the majority of folk songs. The context of their performance is less prescriptive — it is not tied to a certain calendar, domestic, or family event. Their functions are mainly entertainment, communication, and perspective. These songs were sung outdoors in the summer, mostly in the evening, and during periods of monotonous works in the winter (for example, while spinning or embroidery). Songs with serious historical content were mostly sung by men while love songs were sung mostly by young people.

Non-ritual songs are commonly divided by epic, lyrical (on topics relating to premarital communication, family relations, etc.), and religious (psalms) subject matter. Folk epics (dumy, historical songs, ballads, songs-chronicles) carry historical folk knowledge and played the role of ‘oral literature’ that included historical, domestic, and criminal narratives. Dumy constitute a unique Ukrainian folk genre and are sung in a style that falls outside the typical corpus of epics. Dumy and psalms, in addition to historical and dance songs and melodies, composed the repertoire of blind, itinerant singers and musicians who performed them accompanied by kobza, lyre, and bandura. The psalmists could be both women and men, but dumy were the exclusive jurisdiction of kobzari (‘kobza players’), lyrnyki (‘lyre players’), and bandurysty (‘bandura players’).

Epic songs include songs on historical themes (history, the story of Cossacks) and ballads — these songs often depict narratives and extraordinary events (for example, daughter-in-law turns into a poplar after mother-in-law curses her, husband kills his wife at the urging of his mother, accidental incest, brother sells his sister, a girl poisons an unfaithful lover, etc.). Zhorstokyi romans (‘cruel romance’) are a ‘low’ song genre adjacent to ballads. This genre came to the village from the city, working-class settlements, and suburbs, and occupy a distinct place in the rural repertoire.

Songs geographically connected to the Carpathian region often contain plots that chronicle troubling local accidents, public affairs, and criminal acts. This genre is sometimes called ‘people's newspapers’ (‘Listen, good people, what I want to say, // To sing a little about what occurred abroad’). This is a relatively new folk genre. It was first recorded at the turn of the 19th-20th century. These songs were composed by talented individuals whose names were often preserved. The song genre known as kolomyiky is common in regions of western Ukraine.

Lyrical folk songs have mainly love, philosophical, and contemplative themes. This was a favourite genre of both performers and listeners as the lyrics were adaptable and open to contributions by the audience. At the same time, there are a number of popular folk songs that became an integral part of Ukrainian celebrations, for example: ‘Galia carries water’, ‘A Cossack rode through the city // A stone cracked under his horse’s hoof’, ‘Oh, a lake in the field, // A bucket floated there’, ‘Black Sea sailor, mother, Black Sea sailor // Brought me barefoot to the frost’, ‘Of the high mountain pigeons take off, // I have not experienced luxury, the summers are over’, and ‘Thorns bloom, thorns bloom’.

Some categories of folk songs demonstrate the prevalence of hybridized themes such as epic-narratives and lyrical-dramas. However, they are united by their belonging to the repertoire of a certain corporate community, for example, Chumaks, recruits, soldiers, burlaks, and servants (chumatski, rekrutski, soldatski, burlatski, naimytski, zarobitchanski, including emigrant/immigrant songs).

It is customary to categorise children's folklore separately. These are works performed by adults for children, or by children themselves. Among these pieces,the richest category is kolyskovi (‘lullabies’).

Today, researcher-theorists and singer-practitioners are increasingly finding old songbooks in the archives. Thus, it can be concluded that many historical and lyrical pieces that were considered folk songs had a literary origin. ‘I look at the sky’ and ‘There is a high mountain standing’ are examples of prominent verses that were performed on a mass scale. Songwriters who composed pieces that were assimilated by folk tradition in the 20th century (striletski, povstanski) are well known.

Communities of young men and young women played an important role in the creation and performance of folk songs In the 20th century, amateur folk bands tried to preserve musical traditions, despite certain ideological pressures.The culture of authentic singing has somewhat suffered, as conductors have tried to ‘ennoble’ the performance of folk music with a new style; this has been promoted and even imposed in cultural and educational institutions. Nevertheless, the end of the 20th century witnessed a growing interest in authentic singing by both performers and listeners. From the second half of the 19th century to the present day, folklorists, linguists, and ethnomusicologists have played a special role in preserving folk songs. Today, relics of traditional folk songs can still be heard among the oldest performers in Ukraine.